Scientists think they've filled an important gap in whale evolution - the fossilised remains of a specimen that lived around 36.4 million years ago, and is thought to be one of the first whales to use large, sieve-like combs called baleen instead of teeth to filter their food.

Today, baleen whales (or mysticeti) are among the largest mammals on Earth, including blue and humpback whales. Although researchers know that at some point, they shared a common ancestor with toothed whales such as sperm and beaked whales, until now, how these two groups diverged has remained a mystery.

But an analysis of fossilised remains uncovered back in 2010 on Peru's southern coast could help fill in the gaps in the family history.

The newly identified species has been named Mystacodon selenensis, and it's estimated to be around 2 million years older than the previous earliest known example of a baleen whale.

That means it's providing researchers with all kinds of clues about how baleen whales ended up with their unique feeding structure.

"This [split in the family tree] has been dated to about 38 or 39 million years ago years ago," lead researcher Olivier Lambert from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences told The Guardian.

"The whale we discovered here has been dated to 36.4 [million years ago], so it is only 2 to 3 million years younger than this presumed origin."

Cetaceans are a diverse group of aquatic mammals that include modern whales, dolphins, and porpoises, and they're are like the poster child for evolution.

About 55 million years ago, these weird mammals that looked more like dogs than dolphins split into a group that would one day give us hippos, and another that would give us humpbacks.

Populations of these whale ancestors adapted to aquatic living by becoming more streamlined, developing snouts and teeth that could snap up fish or pick through sediment, and gradually developing legs that could paddle better than they could walk.

About 41 million years ago, a group of animals called basilosaurids became the first whale relative to live full-time in the water, with front legs that had flattened into flippers, tiny hind limbs, and a body that could undulate through the water, complete with a tail fin.

They also had smallish brains, so probably weren't overly social, and lacked the structures that allow modern toothed cetaceans to do that neat echolocation trick.

Within the next 10 million years, cetaceans branched into two varieties – one that eventually gave us what we call toothed whales, or odontoceti, and another giving us mysticeti, or baleen whales.

That's not to say all mysticeti ancestors had mouths bristling with keratin krill-combs called baleen like today's humpbacks and blue whales – many still possessed teeth.

"There's big-toothed things, there's little-toothed things and there's toothless things, all at once," Mark D. Uhen, a palaeontologist who wasn't part of the research, explained to Sarah McQuate at Nature.

By 23 million years ago, the branch giving us today's mysticeti were all filter feeders, using long strips of baleen to sift tiny marine life from large mouthfuls of sea water.

It isn't entirely clear what conditions helped baleen win out in this one group of whales – especially while the other branch stuck with teeth – which is why finds such as this are so important.

"We will look inside the bone to see if we can find some changes that may be correlated with this specialised behaviour," says Lambert.

Previously, the oldest known baleen whale fossil was 34 million years old, belonging to a specimen called Llanocetus denticrenatus.

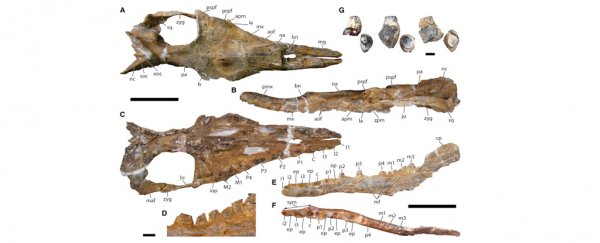

This even older fossil roughly the size of a modern dolphin has been given the scientific name Mystacodon selenensis, and displays characteristics that fall part-way between the toothed basilosaurids and more recent baleen whales.

"For example, this early mysticete retains teeth, and from what we observed of its skull, we think that it displays an early specialization for suction feeding and maybe for bottom feeding," said Lambert.

It also still had tiny vestigial hind legs that would have protruded from its body – visible remnants of limbs that later disappear altogether.

What's interesting is it demonstrates this gradual loss of hind limb happened independently in both cetacean branches.

While basilosaurids were active hunters, much like orcas are today, Mystacodon's teeth and mouth showed signs of being better suited to sucking up smaller animals from the ocean floor, possibly representing a step between hunting bigger prey and sifting smaller catches.

"Among marine mammals, when a slow-swimming animal is living close to the sea floor, generally the bone is much more compact, and this is something we want to test with these early mysticetes," says Lambert.

Additional research on the fossil, as well as uncovering even more intermediate specimens, will continue to fill in the details on the whale's evolutionary history, and show why we now have two radically different branches of massive marine mammals.

And there's still plenty to find – until now, most discoveries have been in the Northern Hemisphere.

"However, key steps in whales' evolution happened in areas now occupied by India, Pakistan, Peru, and even Antarctica," says Lambert.

Watch this space.

This research was published in Current Biology.