There are some freaky eyeballs out there in the wider animal kingdom, but a type of marine worm has scientists boggling.

They're called alciopid polychaete worms, and their eyes are simply enormous. Together, the eyes are 20 times the weight of the rest of the animal's head; for a human, that would be around 50 kilograms (110 pounds) per eye.

We've known about these ginormous peepers for a while; what scientists wanted to know is what the worms see with them.

"We set out to unravel the mystery of why a nearly invisible, transparent worm that feeds in the dead of night has evolved to acquire enormous eyes," says marine biologist Michael Bok of Lund University in Sweden. "As such, the first aim was to answer whether large eyes endow the worm with good vision."

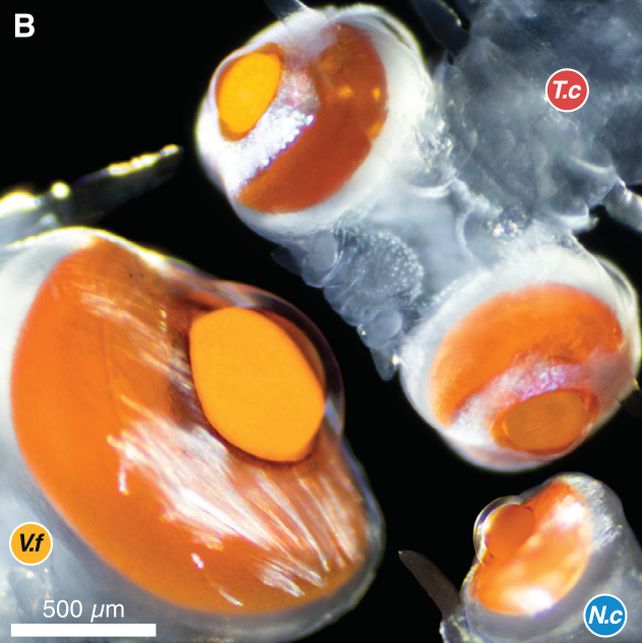

Their work involved a detailed investigation of the vision of three species of nocturnal marine worms from the Mediterranean: Torrea candida, Vanadis cf. formosa, and Naiades cantrainii, each of which sports a giant pair of bulbous peepers.

The researchers conducted optical, morphological, and electrophysiological studies of the eyes of these animals in granular detail. And the results revealed that the Alciopidae family of polychaete worms to which all three species belong are able to see small or distant objects and track their movement.

Given only vertebrates, arthropods, and cephalopods had previously been known to have object vision, this is really something unusual. Most other polychaete worms have low-resolution basic vision, or directional photoreception that only detects the presence of light and the direction it comes from.

"This is the first time that such an advanced and detailed view has been demonstrated beyond these groups," says neuro and marine biologist Anders Garm of the University of Copenhagen.

"In fact, our research has shown that the worm has outstanding vision. Its eyesight is on a par with that of mice or rats, despite being a relatively simple organism with a miniscule brain."

It's still not clear why a creature that is active at the bottom of the ocean at night needs such refined visual acuity. And it really does seem to; while the worm's body is transparent enough to allow it to hide, its eyes need to remain opaque enough to absorb light. That means that the eyes must confer a benefit that offsets the risk of being noticed by passing predators.

We don't know for sure what that benefit is. But research conducted nearly 50 years ago offers a clue. In 1977, scientists found that the eyes of these worms are most sensitive in detecting ultraviolet wavelengths. This suggests that nocturnal marine life has a secret we're yet to uncover.

"We have a theory that the worms themselves are bioluminescent and communicate with each other via light. If you use normal blue or green light as bioluminescence, you also risk attracting predators. But if instead, the worm uses UV light, it will remain invisible to animals other than those of its own species. Therefore, our hypothesis is that they've developed sharp UV vision so as to have a secret language related to mating," Garm explains.

"It may also be that they are on the lookout for UV bioluminescent prey. But regardless, it makes things truly exciting as UV bioluminescence has yet to be witnessed in any other animal. So, we hope to be able to present this as the first example."

The research has been published in Current Biology.