A distant galaxy located some 555 million light-years away has long intrigued scientists due to variations in how brightly it shines. But a recent darkening suggests that something strange is afoot in the Markarian 1018 galaxy.

Scientists think that the supermassive black hole at the centre of Markarian 1018 could be dimming the galaxy due to a lack of fuel. But what force in the Universe could disrupt the food supply of a supermassive black hole like this?

Well, an international team of researchers thinks it could be the result of a rival supermassive black hole setting up camp nearby, and hogging all the chow for itself.

Astronomers first detected Markarian 1018 back in the 1970s, when it was relatively dim, but just five years later, new observations showed that the galaxy appeared to be shining much more brightly.

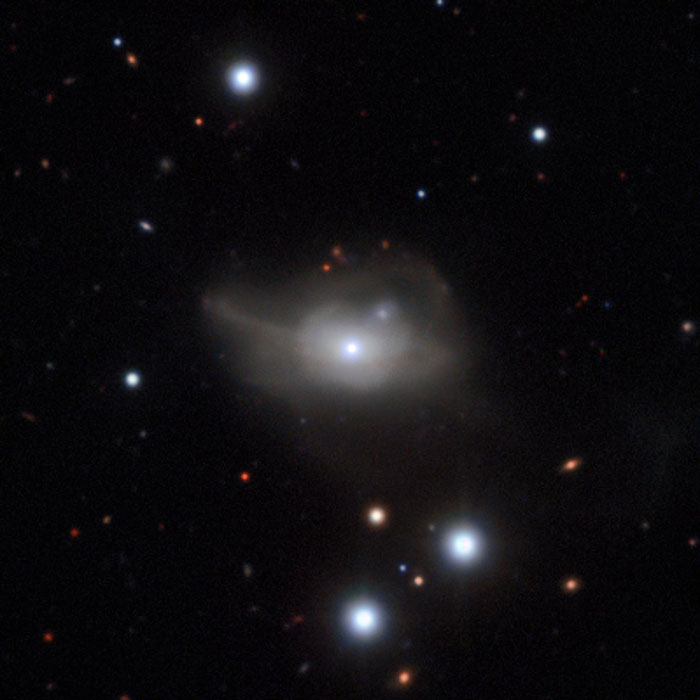

Markarian 1018. Credit: ESO/CARS survey

Markarian 1018. Credit: ESO/CARS survey

Galaxies that shine brightly like this are called active galaxies, and scientists think the reason they emit so much light is because they have supermassive black holes at their centre.

The idea is that as material gets sucked into a black hole, it becomes extremely hot and starts to glow fiercely – a process that scientists call accretion.

Accretion is responsible for the brightest active galaxies – including the brightest of all (quasars), and what are known as Seyfert galaxies.

When Markarian 1018 was observed shining brightly, it was categorised as a Type I Seyfert, meaning it produced ultraviolet light and X-rays in addition to visible light.

But when the researchers took another look at the galaxy last year using the European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope, that bright light had all but disappeared.

"We were stunned to see such a rare and dramatic change in Markarian 1018," says lead researcher Rebecca McElroy from the University of Sydney in Australia.

Markarian 1018 was already in rare company for having changed its level of brightness once before, as scientists have only observed the phenomenon taking place about 20 times ever. But for it to happen twice? That makes it almost entirely unique among the star systems we've so far observed.

"It is very exciting to look at your data and see something you weren't expecting," says McElroy.

As for what's behind this galactic dimming, it's too early to know for sure, but the data so far suggests that it's not just a case of Markarian 1018 running out of matter to feed the black hole at its centre.

"It looks like something slightly more dramatic has gone on, and something has actually disrupted the inflow of fuel to the centre of the galaxy," McElroy told James Bullen at the ABC.

And that something, the scientists estimate, is likely to be another supermassive black hole.

The researchers think that at some point in the last billion years, Markarian 1018 began to merge with another galaxy. Not just any galaxy, but another active galaxy. And you know what that means.

"When galaxies get close to one another, they begin to orbit together and eventually coalesce," McElroy told John Ross at The Australian.

"Most galaxies have supermassive black holes, and if you throw two galaxies at each other there are going to be two black holes that will eventually sink to the centre."

In other words, it's possible that this other supermassive black hole has encroached upon the original void at the centre of Markarian 1018, and is now depriving it of fuel – thereby preventing accretion, and the resultant shining.

Sucks to be Markarian 1018's black hole, I guess.

The researchers acknowledge that it's only a hypothesis at this point, but are eager to get to the bottom of Markarian 1018's strange activity. To do so, they'll be continuing their investigation, using NASA's Hubble and Chandra observatories, in addition to other space telescopes.

"We have been able to rule out a couple of scenarios but data are still flooding in," says McElroy, "so the team is really keen on finding out more about the physics that drive the behaviour of this unusual galaxy".

The findings appear in two papers, here and here, in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.