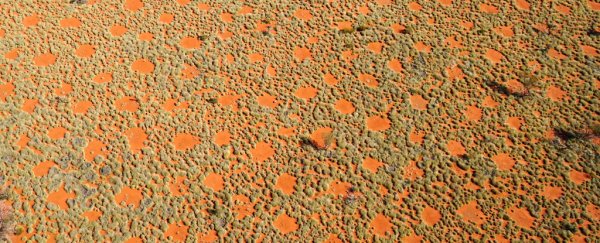

From above, the Namib Desert in Africa appears afflicted by disease, pocked with patches of bare earth that are either touched by the gods, the dead, or the wildlife, depending on who you ask.

Science had all but closed the book on these mysterious 'fairy circles', placing the blame squarely on the soil. To remove all doubts, researchers turned to the skies for more evidence, only to discover the story might not be so clear cut after all.

Ecologist Stephan Getzin from the University of Göttingen in Germany has been front and centre of the fairy circle debate for years after first encountering them in Namibia as an undergrad.

His most recent research could be the final nail in the coffin for (unfounded) suggestions that termites are to blame for these strange rings. But it's also adding new details to theories describing how these strange spaces in the vegetation actually form.

Namibia's vast stretch of fairy circles had already been perplexing ecologists for decades; then, Getzin was alerted to the existence of a similar expanse of vegetation in the arid Pilbara region of Western Australia in 2014, providing him with the evidence he needed for his own hypothesis.

In 2017, we were given an answer - the fairy circles in both Namibia and the Pilbara are caused by plants competing for water around patches of soil that channel water at a faster rate.

Well, that's part of the story. Science is rarely so simple, and questions remained on whether termites commonly found near these empty patches are merely tourists or tiny lumberjacks contributing to the desolation.

To clear the air once and for all, Getzin and fellow researchers from Israel and Australia systematically surveyed dozens of fairy circles near the Western Australian town of Newman, digging 154 holes over a length of 12 kilometres (7.5 miles).

Not only did they find the soil was similarly packed with the same levels of clay inside the circles, they failed to find the termite highways that would suggest their activity had much of a role in the development of the circles.

To make doubly sure, they also mapped large squares of landscape using drones, marking out zones where the vegetation was clearly broken down by harvester termites.

"The vegetation gaps caused by harvester termites are only about half the size of the fairy circles and much less ordered," says Getzin.

"Overall, our study shows that termite constructions can occur in the area of the fairy circles, but the partial local correlation between termites and fairy circles has no causal relationship."

But this revisit of Namibia's patchwork of spotty vegetation has also added new details to their formation.

Until recently, most of the research had concentrated on fairy circles of relatively consistent size and distribution. Getzin was curious to know what environmental conditions described the threshold of their formation.

Using imagery from Google Earth, Getzin and his team identified a range of structures that weren't quite the usual fairy circle size and shape, but still indicated a similar formation.

Some were more than 20 metres (66 feet) across, dwarfing the usual maximum diameter of roughly 12 metres (39 feet). Others were stretched out in drainage lines, or formed in unusual areas like car tracks.

They might not be as eye-catching as polka-dotted plains stretching to the horizon, but these awkward cousins to the more famous fairy circles help better define the kinds of conditions that give rise to the phenomenon.

"Here our soil moisture studies showed that under such varied conditions the fairy circles function less as water reservoirs than under typical homogeneous conditions where they are extremely well ordered," says Getzin.

Science has a habit of keeping arguments alive long after evidence looks conclusive. No doubt there's more to be said about these odd circles in the outback, but we can probably declare them a lot less mysterious.

This research was published in Ecosphere and the Journal of Arid Environments.