Over the past decade, astronomers have made huge advances in detecting planets orbiting distant stars - or exoplanets. We now know that 1,800 exist, and we're finding more all the time.

But, contrary to what you might think, you don't actually need a fancy telescope to discover these distant worlds. Amateur astronomer David Schneider has managed to spot a planet in a star system around 63 light-years away using just a digital camera, some plywood, basic electronics and a zoom lens.

In the video above, he explains how you can do the same with easy to access and relatively cheap equipment.

As science educator and futurist Federico Pistono commented on Google+:

"So this guy detected an exoplanet with household equipment, some plywood, an Arduino, and a normal digital camera that you can buy in a store. Then made a video explaining how he did it and distributed it across the globe at practically zero cost.

Now tell me we don't live in the future."

So how does it all work? We're able to "see" planets so far away by actually looking at the stars they orbit - when a planet passes in front of their star it causes a dip in the star's brightness. Monitoring this temporary dimming caused by an exoplanet is known as transit detection.

And as Schneider explains in IEE Spectrum, in order to be able to detect this transit of an exoplanet from your home, all you really need is a regular digital camera with a store-bought 300-millimetre telephoto lens.

Once you've got the equipment, one of the toughest parts is working out how to get your camera to track a star over a long period of time as Earth rotates.

Sure, you can buy commercial star trackers out there, but Schneider came up with a cheaper option - making his own with two pieces of plywood hinged tougher, and a Arduino microprocessor to automatically tilt the device.

When you've got your device set up in a secure place, all you need to do is get a star lined up in your viewfinder (which isn't as easy as it sounds) and then set your camera up to take a sequence of photos. As Schneider writes in IEEE Spectrum, the Czech Astronomical Society provides a useful online tool (which is currently down for scheduled maintenance, but will be back up soon) for determining when you'll be able to see the orbit of an exoplanet.

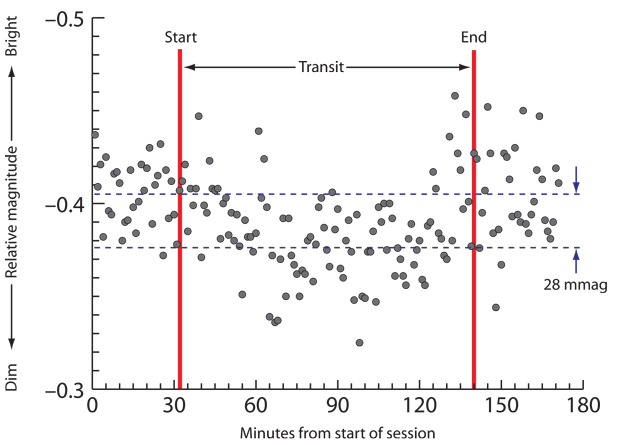

Schneider collected images of a binary star system called HD 189733 over a three-hour period and then used free online software called Iris to calculate the changes in the star's brightness, and then mapped the data in Excel.

The graph (below) showed a clear dip in brightness and proved that he'd been able to detect the orbit of a planet outside of our Solar System using nothing his home set up, which, when you think about it, is pretty astounding.

For more details on how to build your own DIY exoplanet detector, read Schneider's instructional piece over at IEEE Spectrum.

Now get out there and start discovering.

Source: IEEE Spectrum, IEEE Spectrum's YouTube