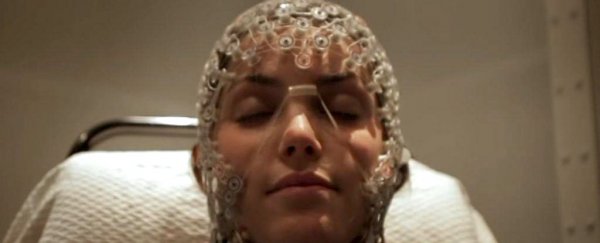

A sleeping brain can form fresh memories, according to a team of neuroscientists. The researchers played complex sounds to people while they were sleeping, and afterward the sleepers could recognise those sounds when they were awake.

The idea that humans can learn while asleep, a concept sometimes called hypnopaedia, has a long and odd history. It hit a particularly strange note in 1927, when New York inventor A. B. Saliger debuted the Psycho-phone. He billed the device as an "automatic suggestion machine."

The Psycho-phone was a phonograph connected to a clock. It played wax cylinder records, which Saliger made and sold.

The records had names like "Life Extension," "Normal Weight" or "Mating." That last one went: "I desire a mate. I radiate love … My conversation is interesting. My company is delightful. I have a strong sex appeal."

Thousands of sleepers bought the devices, Saliger told the New Yorker in 1933. (Those included Hollywood actors, he said, though he declined to name names.) Despite his enthusiasm for the machine - Saliger himself dozed off to "Inspiration" and "Health" - the device was a bust.

But the idea that we can learn while unconscious holds more merit than gizmos named Psycho-phone suggest. In the new study, published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, neuroscientists demonstrated that it is possible to teach acoustic lessons to sleeping people.

"We proved that you can learn during sleep, which has been a topic debated for years," said Thomas Andrillon, an author of the study and a neuroscientist at PSL Research University in Paris. Just don't expect Andrillon's experiments to make anyone fluent in French.

Researchers in the 1950s dismantled hypnopaedia's more outlandish claims. Sleepers cannot wake up with brains filled with new meaning or facts, Rand Corp. researchers reported in 1956. Instead, test subjects who listened to trivia at night woke up with "non-recall."

(Still, the Psycho-phone spirit endures, at least in the app store, where hypnopedia software claims to promote foreign languages, material wealth and martial arts mastery.)

Yet success is possible, if you're not trying to learn dictionary definitions or kung fu. In recent years, scientists have trained sleepers to make subconscious associations.

In a 2014 study, Israeli neuroscientists had 66 people smell cigarette smoke coupled with foul odours while they were asleep. The test subjects avoided smoking for two weeks after the experiment.

In the new research, Andrillon and his colleagues moved beyond association into pattern learning. While a group of 20 subjects was sleeping, the neuroscientists played clips of white noise. Most of the audio was "purely random," Andrillon said. "There is no predictability."

But there were patterns occasionally embedded within the complex noise: sequences of a single clip of white noise, 200 milliseconds long, repeated five times.

The subjects remembered the patterns. The lack of meaning worked in their favour; sleepers can neither focus on what they're hearing nor make explicit connections, the scientist said. This is why nocturnal language tapes don't quite work - the brain needs to register sound and semantics.

But memorising acoustic patterns like white noise happens automatically. "The sleeping brain is including a lot of information that is happening outside," Andrillon said, "and processing it to quite an impressive degree of complexity."

Once the sleepers awoke, the scientists played back the white-noise recordings. The researchers asked the test subjects to identify patterns within the noise. It's not an easy task, Andrillon said, and one that you or I would struggle with. Unless you happened to remember the repetitions from a previous night's sleep.

The test subjects successfully detected the patterns far better than random chance would predict.

What's more, the scientists discovered that memories of white-noise pattern formed only during certain sleep stages. When the authors played the sounds during REM and light sleep, the test subjects could remember the pattern the next morning.

During the deeper non-REM sleep, playing the recording hampered recall. Patterns "presented during non-REM sleep led to worse performance, as if there were a negative form of learning," Andrillon said.

This marked the first time that researchers had "evidence for the sleep stages involved in the formation of completely new memories," said Jan Born, a neuroscientist at the University of Tübingen in Germany, who was not involved with the study.

In Andrillon's view, the experiment helps to reconcile two competing theories about the role of sleep in new memories: In one idea, our sleeping brains replay memories from our waking lives.

As they're played back, the memories consolidate and grow stronger, written more firmly into our synapses. In the other hypothesis, sleep instead cuts away at older, weaker memories. But the ones that remain stand out, like lonely trees in a field.

The study indicates that the sleeping brain can do both, Andrillon said. They might simply occur at separate moments in the sleep cycle, strengthening fresh memories followed by culling.

A separate team of neuroscientists had suspected that the two hypotheses might be complementary. But until now they did not have any explicit experimental support.

"It is a delight to see these results, since we proposed already, quite a few years ago, that the different sleep stages may have a different impact on memory," said Lisa Genzel, a neuroscientist at Radboud University in the Netherlands. "And here they are the first to provide direct evidence for this idea."

Not all neuroscientists were so convinced. Born, an early proponent of the idea that sleep strengthens and consolidates memories, said this study showed what happens when we form memories while asleep.

The average memory - a recollection from a waking experience - might not work in the same way, he said. "I would be skeptical about inferring from this type of approach to what happens during normal sleep."

Andrillon acknowledged the limitations of this research, including that the scientists did not directly measure synapses.

"We interpret our results in the light of cellular mechanisms," he said, meaning strengthening or weakening of synapses, "that we could not directly measure, since they require invasive recording methods that cannot be applied in humans."

When asked whether understanding the roles of sleep cycles and memory could lead to future sleep-hacks, a la the Psycho-phone, Andrillon said, "We are in the big unknown." But, he noted, sleep is not just about memory. Trying to hijack the recommended seven-plus hours of sleep could disrupt normal brain function.

Which is to say, even if you could learn French while asleep, it might ultimately do more harm than good. "I would be very cautious about the interest in this kind of learning," he said, "whether this is detrimental to the other functions of sleeping."

2017 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.