For the first time, engineers have demonstrated how 'bubbles' of lighter grains can form in sand, just as they can in other fluids - even though granular materials tend towards mixing.

Although individual grains of sand are solid, when you get a lot of them, they behave surprisingly like a fluid - think of falling sand dunes, avalanches, or sand flowing through an hourglass. These are called granular materials, and the physics of how they flow are still somewhat mysterious compared to fluids.

In fluid dynamics, there is a mechanism called the Rayleigh-Taylor (RT) instability. It happens in the interface between two fluids when they are of different densities, and the lighter fluid is pushing against the heavier one - such as oil rising through water, or supernova explosions where lighter gas pushes into the denser surrounding envelope.

Nothing like it had ever before been seen in a granular material. But that is strikingly similar to what engineers from Columbia University and ETH Zurich have discovered.

"We think our discovery is transformational," said chemical engineer Chris Boyce of Columbia.

"We have found a granular analog of one of the last major fluid mechanical instabilities. While analogs of the other major instabilities have been discovered in granular flows in recent decades, the RT instability has eluded direct comparison."

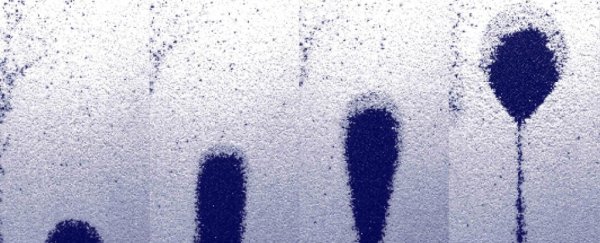

The team found that both vibration and upward gas flow through a granular material can produce a similar process to RT instability. Lighter grains start to rise through the heavier grains in fingers (a long thin shape) and bubbles that leave a trail of particles in their wake.

It's very similar to how oil rises through water, but with one huge difference. Oil and water don't like to mix. Sand does.

Using both experimental and computational modelling approaches, the researchers were able to figure out how bubbles consisting of lighter grains of sand rose through a layer of heavier grains.

It's because the clusters of lighter, larger grains allow gas (in this case, air) to flow through more easily than the heavier, smaller grains. This increases tension between the upward drag force created by the gas flow and the downward contact forces, creating an RT-like instability.

While the result is similar, the process is actually different from the mechanism behind RT instabilities in liquids.

And the team observed a few other interesting things, too. For instance, the gas flow generates other instabilities, such as what the researchers describe in their paper as "the cascading branching of a descending granular droplet".

This is similar to the RT instability observed when dropping dye in water, but not entirely, since we're working with sand here.

The weight of the descending droplet of heavier grains creates force chains below, which the drop can't pass through. So it splits into branches on its way down, a bit like lightning.

The other finding was that the RT-like instability in sand can arise under a wide range of gas flow and vibration conditions - which, among other things, could help understand the subterranean processes at play during Earth tremors.

"Our findings could not only explain geological formations and processes that underlie mineral deposits, but could also be used in powder-processing technologies in the energy, construction, and pharmaceuticals industries," Boyce said.

"We are especially excited about the potential impact of our findings on the geological sciences - these instabilities can help us understand how structures have formed over the long history of the Earth and predict how others may form in the future."

So, that's Lightning Sand demystified. Rodents of Unusual Size were discovered in 2017. Now we just need Flame Spurts…

The research has been published in PNAS.