When it comes to black holes, the past couple of years have seen a firestorm of disagreements about event horizons, firewalls, and the very nature of black hole life and death erupting between cosmologists. It's admittedly been a quiet firestorm, with papers here and there carefully arguing their positions while being respectful of opposing views, but that still counts as a firestorm in science.

Some people thought that the gravitational waves observed earlier this year could put an end to the dispute, but a group of physicists now warns that we shouldn't be so quick to jump to conclusions.

The arguments centre around two related disagreements over what we're actually talking about when we call something a ' black hole'.

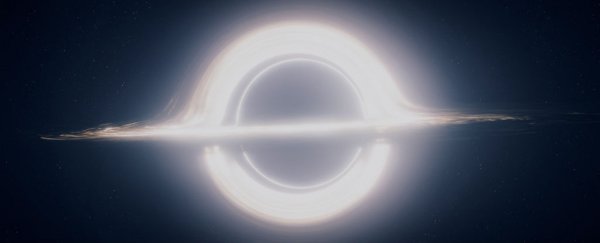

The first is over what happens when something falls into a black hole. Traditionally, black holes are thought to be objects with a gravitational force so strong, light isn't even going fast enough to escape their clutches. And if light - the fastest thing in the Universe - can't escape, then neither can anything else.

A black hole is usually defined by its event horizon - the outline of the region in space where gravity is strong enough to hold light down. You wouldn't even necessarily notice as you passed over the event horizon of a black hole, since it's just a place in space like any other. You'd only notice when you tried to escape.

But a few years ago, a couple of papers suggested that this very simplified view leads to some problems that can't be resolved with our current understanding of the laws of physics.

Instead, they said, there must be something special about the event horizon: just after something passed over the event horizon, it would be scrambled and burnt up beyond recognition by something called a firewall. These firewalls seemed to eliminate the theoretical problems, but they were a pretty weird solution – and not everyone was on board.

One of those not on-board was Stephen Hawking, who thought it was ridiculous. Hawking and those who agreed with him maintained that there was nothing special about the edge of a black hole.

But then Hawking went a step further, adding fuel to the second part of the debate. In his quest to disprove the firewall, he ended up with a black hole without an event horizon.

This turned the definition of a black hole upside-down: without the event horizon - the place beyond which nothing can ever escape the black hole - what even defines a black hole? Physicists weren't exactly scrambling to the table with answers.

At the same time, there were some alternatives to black holes being developed that might still have extreme gravity but wouldn't have a point of no return. These strange objects have been dubbed 'black hole mimickers'.

And then there were those who kept black holes with event horizons but still refused to believe the firewall.

All of the different parties converged on the gravitational waves observed by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). At first glance, the gravitational waves seemed like a clear victory for the black-holes-with-event-horizons camp. The pattern of the waves seemed to exactly match their predictions of what it should look like when two black holes with event horizons collide to form another black hole with an event horizon.

They were particularly excited about the 'ringdown' - when the final black hole sheds some energy and settles down after all the excitement of the collision. The ringdown, they said, precisely matched what they expected and didn't match other contradictory predictions.

But the authors of a new paper say we can't be quite so sure. They showed that the gravitational waves LIGO detected could have been made by any of those black hole mimickers - the objects that have gravity like a black hole without having an event horizon. So it seems like we're back to square one.

But there is hope for distinguishing between the different hypotheses. They still disagree when it comes to the ringdown, but the disagreements are going to take better measurements to resolve. With better measurements of gravitational waves and of the ringdown, we should be able to answer these fundamental questions about the nature of black holes.

So don't worry. LIGO is on the case.

The paper has been published in Physical Review Letters.