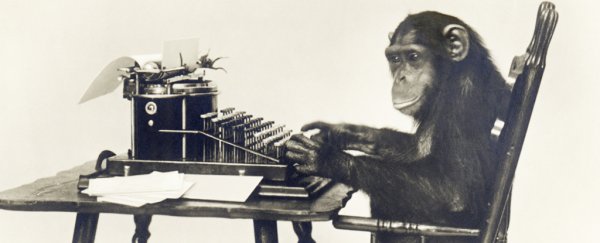

There's an old theorem about monkeys, typewriters, and Shakespeare, suggesting that, with an infinite amount of time, a monkey randomly tapping away at a typewriter would actually recreate the famous playwright's complete works.

And now scientists have combined all three for real. Not to study randomness, but to pioneer new ways of translating our thoughts into written words - by reading brain signals and converting them into movement across a keyboard.

The system, which essentially amounts to typing with the mind, was developed by researchers at Stanford University. The team ran experiments with a group of monkeys, which saw them transcribe text at a rate of up to 12 words per minute.

"Our results demonstrate that this interface may have great promise for use in people," said one of the researchers, Paul Nuyujukian. "It enables a typing rate sufficient for a meaningful conversation."

The monkeys involved in the study didn't suddenly 'learn' to read and understand English, but were instead trained to tap out letters based on what was shown to them on a screen. In addition to typing out Shakespeare (Hamlet), they also reproduced passages from The New York Times.

While the use of similar technology has been demonstrated before, the Stanford researchers say their new system is significantly faster and more accurate than anything else that currently exists, which is why the typing rate is important.

That speed increase is mostly down to improvements in the algorithm converting thought to movement.

In this setup, brainwaves are read with a multi-electrode array, which is implanted in the monkey's brain to record neural signals. But the system isn't looking for fully formed letters or words - instead, it monitors the part of the brain that controls hand actions, such as moving a computer mouse.

By intercepting the brain's commands to move a mouse across a desk, the technology translates those thoughts directly into the movements of a mouse cursor on the screen, so letters can be picked out one by one.

With the addition of some auto-correct features, like those on your phone, the researchers say the system could become even faster.

Brain-sensing has several advantages over eye-tracking typing technology: it's not as tiring on the writer, and it's more practical for those who aren't always able to control facial and eye movements.

The system might be able to work in the long term, too. The monkeys involved in the tests have had their brain-monitoring implants installed for several years now, and the researchers say there have been no noticeable differences in brain activity and no unwanted side-effects.

"The interface we tested is exactly what a human would use," said Nuyujukian. "What we had never quantified before was the typing rate that could be achieved."

While we won't see monkeys writing Shakespeare-quality originals any time soon, the technology could be a great help to people who experience difficulty in typing or speaking.

And it looks like we won't have to wait too long to find out how feasible the system is, as a clinical trial with human participants is now underway.

The findings are published in the Proceedings of the IEEE.