Researchers warn that large parts of biomedical science could be invalid due to a cascading history of flawed data in a systemic failure going back decades.

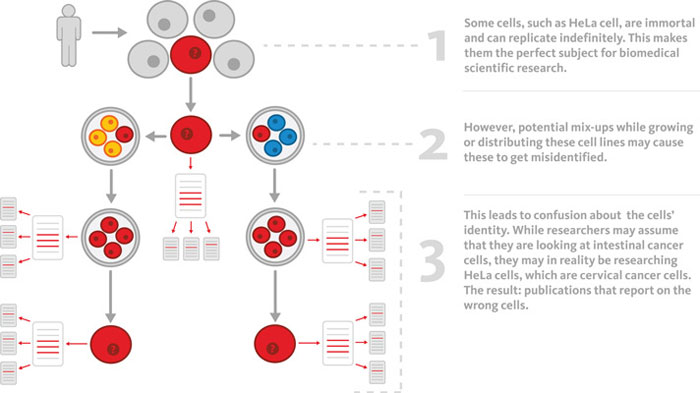

A new investigation reveals more than 30,000 published scientific studies could be compromised by their use of misidentified cell lines, owing to so-called immortal cells contaminating other research cultures in the lab.

The problem is as serious as it is simple: researchers studying lung cancer publish a new paper, only it turns out the tissue they were actually using in the lab were liver cells. Or what they thought were human cells were mice cells, or vice versa, or something else entirely.

If you think that sounds bad, you're right, as it means the findings of each piece of affected research may be flawed, and could even be completely unreliable.

"Most scientists don't intentionally publish findings on the wrong cells," explains one of the researchers, Serge Horbach from Radboud University in the Netherlands.

"It's an honest mistake. The more concerning problem is that the research data is potentially invalid and impossible to reproduce."

Horback and fellow researcher Willem Halffman wanted to know how extensive the phenomenon of misidentified cell lines really was, so they searched for evidence of what they call "contaminated" scientific literature.

Using the research database Web of Science, they looked for scientific articles based on any of the known misidentified cell lines as listed by the International Cell Line Authentication Committee's (ICLAC) Register of Misidentified Cell Lines.

There are currently 451 cell lines on this list, and they're not what you think they are – having been contaminated by other kinds of cells at some point in scientific history. Worse still, they've been unwittingly used in published laboratory research going as far back as the 1950s.

"After an extensive literary study, we believe this involves some 33,000 publications," Halffman explains.

"That means there are more than 30,000 scientific articles online that are reporting on the wrong cells."

Radboud University

Radboud University

Of the 451 cell lines known to be compromised, the most famous contaminating source is what's known as HeLa cells, named after their source, Henrietta Lacks.

In 1951, this 31-year-old mother of five from Virginia died from cervical cancer. But during treatment before her death, cells were taken from Lacks' cervix in a biopsy without her consent.

Later, cell biologist George Otto Gey discovered these cells could be kept alive and grow indefinitely in a lab – as such, HeLa cells became the first immortalised cell line, meaning they didn't eventually die due to cellular senescence.

That everlasting quality made them a valuable research specimen that was distributed across the world, ultimately contributing to the development of cell cloning, the polio vaccine and many other firsts.

It's estimated as many as 20 tonnes of HeLa cells were ultimately grown, with the discovery featuring in a stunning 11,000 patents, but the cells' undying nature came with a hidden cost.

Not only do the cells proliferate, they can also contaminate other exposed cell cultures in laboratory setting, and due to decades of use and misuse in the lab, HeLa cells and other contaminating and immortal cells have been estimated to have tainted up to 36 percent of cell lines scientists use in research.

"It's astonishingly easy for cell lines to become contaminated," ICLAC chair Amanda Capes-Davis explained in 2015 at Retraction Watch.

"When cells are first placed into culture, they usually pass through a period of time when there is little or no growth, before a cell line emerges. A single cell introduced from elsewhere during that time can outgrow the original culture without anyone being aware of the change in identity."

Over decades, these cases of mistaken identity have in turn contaminated some 33,000 scientific papers by Horback and Halffman's count, and it's something that not enough in the research community know about.

"Employees at [biomedical cell distribution] centres recognise the problem, but claim no one will listen to them," says Halffman.

"Sometimes it involves semi-private companies that refuse to disclose anything for fear of reputation or financial damage. The biggest factor by far is pride and fear of reputation damage."

Another contributing issue is pressure to publish, with researchers not having the time or money to verify their cell cultures adequately before they begin their research.

Of course, the tendency to skip that all-important verification is only something that worsens the broader reproducibility crisis plaguing science.

The researchers suggest published research using misidentified cell lines could be clarified with notices that highlight the issue, and say future publications need to implement systems that make the source of the cell lines investigated more transparent.

Whatever course of action the research community decides upon, it's a huge problem to fix – but it's not something we can ignore.

"Nearly half a century after the first concerns about misidentified cell lines, the initiatives to improve authentication need to be complemented by attention to the already contaminated literature," the authors write.

"Our analysis shows that the task is sizeable and urgent."

The findings are reported in PLOS ONE.