A new analysis in more than 3,600 donated brains in the US has singled out malfunctioning tau proteins as the main driver for the cognitive decline and memory loss associated with Alzheimer's disease, offering a new focus for future Alzheimer's treatment and research.

While it's widely recognised that Alzheimer's develops as a result of two malfunctioning proteins, amyloid and tau, just how big a role each of these factors play has been long-debated. Recently, a large portion of research into Alzheimer's has been focussing on amyloid, such as this recent experiment that cleared amyloid build-up from mouse brains and gave them their memory function back.

But researchers at the Mayo Clinic think we've been focussing on the wrong target, because their study suggests that while amyloid proteins do indeed build up as the disease progresses, their presence isn't what's driving it.

"The majority of the Alzheimer's research field has really focused on amyloid over the last 25 years," lead researcher and neuroscientist, Melissa Murray, said in a press release. "Initially, patients who were discovered to have mutations or changes in the amyloid gene were found to have severe Alzheimer's pathology - particularly in increased levels of amyloid. Brain scans performed over the last decade revealed that amyloid accumulated as people progressed, so most Alzheimer's models were based on amyloid toxicity. In this way, the Alzheimer's field became myopic."

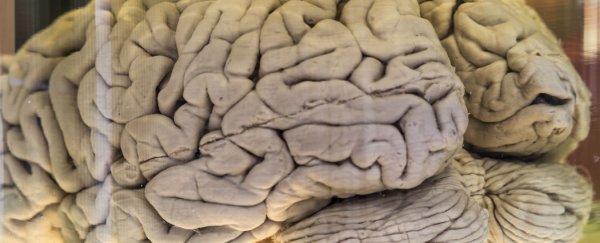

Murray's team examined 3,618 post-mortem brains from the Mayo Clinic's brain bank, and found that 1,375 of their owners had died with varying stages of dementia. They created a timeline for the disease's progression using these brains, and came up with a way to quantify the progression of defective amyloid and tau build-up along the way.

Next, they analysed brain scans taken of amyloid protein clusters in patients prior to death and compared these to the measures they took from the post-mortem brain examinations. Together, these analyses revealed that the severity of tau - not amyloid - malfunction predicted age-related onset of cognitive decline, mental deterioration, and Alzheimer's duration.

Reporting in the journal Brain, the researchers say they found a strong link between the build-up of amyloid and a decline in cognition, but as soon as they took the severity of the tau malfunction into account, this link disappeared. And some of the brains were found to have amyloid build-up without showing signs of cognitive decline.

"Tau can be compared to railroad ties that stabilise a train track that brain cells use to transport food, messages and other vital cargo throughout neurons. In Alzheimer's, changes in the tau protein cause the tracks to become unstable in neurons of the hippocampus, the centre of memory. The abnormal tau builds up in neurons, which eventually leads to the death of these neurons.

Evidence suggests that abnormal tau then spreads from cell to cell, disseminating pathological tau in the brain's cortex. The cortex is the outer part of the brain that is involved in higher levels of thinking, planning, behaviour and attention - mirroring later behavioural changes in Alzheimer's patients. Amyloid, on the other hand, starts accumulating in the outer parts of the cortex and then spreads down to the hippocampus and eventually to other areas."

While the team certainly doesn't recommend ignoring amyloid clusters as key indicators of Alzheimer's progression, they urge future research to focus on what's going on with the tau proteins, in hopes that we can figure out how to detect and halt the progression of the disease.