NASA spacecraft OSIRIS-REx is well on its way to asteroid Bennu. It launched just over a year ago, on 8 September 2016, but it just needed a little extra push from Earth's gravity to get it the rest of the way there.

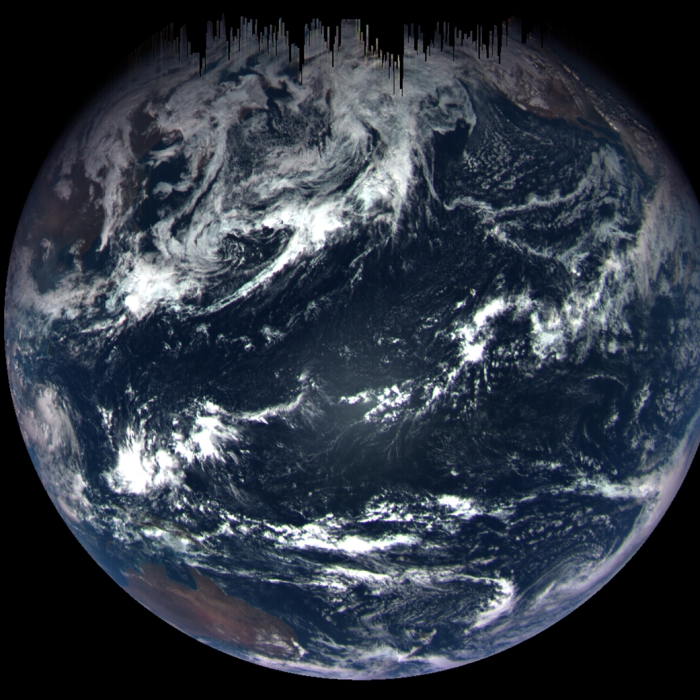

That flyby took place on 22 September, and the OSIRIS-REx team took the opportunity to test and calibrate the spacecraft's instrumentation. And now that data is in - a gorgeous colour-composite snapshot of Earth, taken by OSIRIS-REx's MapCam at a distance of 170,000 kilometres (106,000 miles) away.

The spacecraft captured mostly the Pacific Ocean, but all the way in the bottom left, you can see the familiar shape of Australia, and the Mexican state of Baja California in the top right. Above Australia in the top right is China.

At the very top of the image, dark vertical lines are caused by the short exposure times. OSIRIS-REx's instrumentation was built for imaging Bennu, which is a lot darker than Earth. To compensate for Earth's brightness, the camera took really short exposures. These lines should not appear on images of Bennu.

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/University of Arizona

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/University of Arizona

Bennu's orbital period is slightly longer than Earth's, at 436.63 days, but its distance from Earth varies.

Getting a spacecraft to meet with it will be a feat of very careful, exact calculation, skill and yes, a little bit of luck.

Without using Earth's gravity as a slingshot, OSIRIS-REx would not be able to make it to Bennu, where it will make history by returning asteroid samples to Earth for study. This is called a gravity assist, or slingshot - the spacecraft uses the gravity of a planet to gain velocity and swing into a wider trajectory.

The Voyager spacecrafts used this manoeuvre, as did Cassini, on their journeys beyond the solar system and into Saturn's orbit respectively.

OSIRIS-REx's slingshot manoeuvre increased the spacecraft's velocity by 3.778 kilometres per second (8,451 miles per hour) and changed the tilt of its orbit around the Sun to match Bennu's.

It's expected to rendezvous with the asteroid in August 2018, and then spend two and a half years collecting data and samples to return to Earth.