Human eyes are not usually thought of as the best of the best in the animal kingdom. Cats can see really well in the dark, and some spiders have 12 eyes to stare back at you.

But a new study suggests we should be pretty happy with our peepers, as the sharpness of our vision is miles above most other animals.

Researchers from Duke University have compared and ranked the eyesight of many different species to work out just how sharp or blurry their vision might be.

Throughout the animal kingdom, most species "see the world with much less detail than we do," said Eleanor Caves, an ecologist who specialises in vision at Duke.

You can't go and ask a fly or an eagle to read out letters on an eye chart. Instead, the researchers looked at the anatomy of the eyes, and used behavioural tests to discover the sharpness of vision for the different animals.

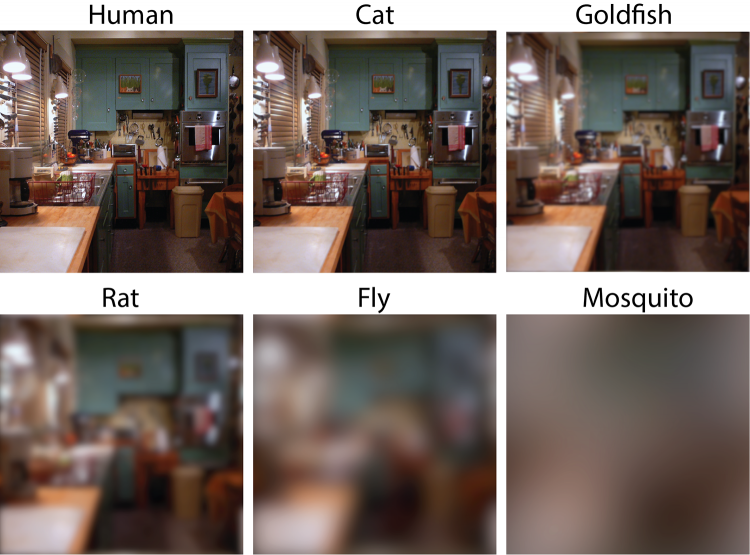

Researchers used a measurement method called 'cycles per degree' to ascertain the sharpness.They then fed that information into a type of software that showed what sort of images these animals would see.

Humans can resolve around 60 cycles per degree – meaning we can see 60 pairs of black and white parallel lines within one degree of vision. More than this, and the lines all smoosh into grey.

The team found that chimps and other primates have about the same level of detail as us. Not a huge surprise.

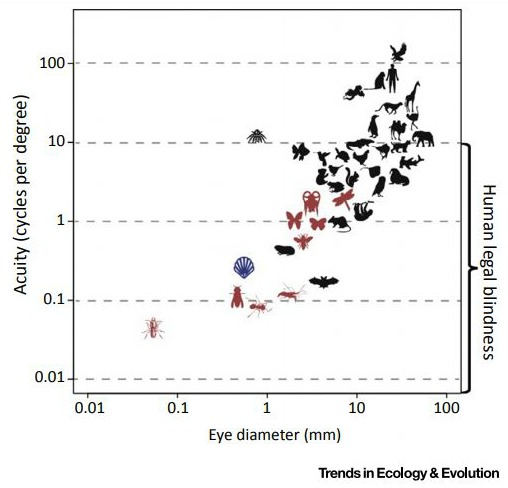

Interestingly, not many animals did better than us, except for a few birds of prey that can see nearly twice the limit of human's clarity of vision.

One example the researchers mention is the Australian wedge-tailed eagle. It can see 140 cycles per degree - useful for spotting small marsupials scurrying across the ground while the birds are thousands of metres high in the sky.

(Eleanor Caves)

(Eleanor Caves)

The researchers found that fish and most birds see about 30 cycles per degree, and elephants can only see about 10.

Ten cycles per degree is the level at which a person is classified as legally blind, but most animals and insects actually fall below that line.

(Trends in Ecology & Evolution)

(Trends in Ecology & Evolution)

Apart from having a visual acuity ranking, what's particularly interesting here is the impact of these findings on what we understand about animal ecology.

For example, if cleaner shrimp have bright colours and antennae that whip when they see a 'client' fish – are they doing it for the benefits of other shrimp, or the fish they are cleaning?

The shrimp themselves "likely cannot resolve one another's colour patterns, even from distances as close as 2 cm … however, both their colour patterns and antennae are visible to fish viewers of various acuities from a distance of at least 10 cm," the team write in the paper.

"Thus, these distinctive colour patterns and antennae-whipping behaviors likely serve as signals directed at clients, despite the inability of cleaner shrimp themselves to distinguish them."

Another example could be the wings of a butterfly - butterflies themselves probably can't see each other's patterns, but birds can.

"The point is that researchers who study animal interactions shouldn't assume that different species perceive detail the same way we do," Caves said.

Now, it's important to note here that spiders, fish or any other animal with limited sharpness might actually see better than the study indicates, due to forms of 'post-processing' in the brain.

The team are only working with eyes at this point, and can't tell what the brain of the animal actually does with the image.

If an eagle were to look at human vision with this same software for example, "it would think our world was blurry - and it's not," Caves told Yasemin Saplakoglu at Live Science.

The software "just tells you what visual information is available."

However, "you can't use information that you never received; if acuity is too low to detect a certain detail, it's probably not something that your brain can then work on further."

So, despite limitations, this study does provide us with fascinating insights into how the rest of the animal kingdom sees the world around us.

The research has been published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution.