All the planets in our Solar System have their charms, but few are as flashy and iconic as Saturn's glorious rings. But, like everything in the Universe, they're not going to last forever - and now planetary scientists have discovered that they're disappearing at an incredibly fast rate.

Well, fast in planetary terms. The rings could disintegrate and fall into Saturn in as little as 100 million years' time, in a process dubbed 'ring rain'.

The discovery was made based on observations from NASA's probes Voyager 1 and 2, which had encounters with Saturn on their way to the outer Solar System in November 1980 and August 1981, respectively.

Combining these with observations from Cassini, in which it analysed the material falling from Saturn's rings down to the planet, has allowed astronomers to calculate exactly how fast the rings are disintegrating.

As it turns out, it's as fast as the maximum rate in the range originally predicted by Voyager.

"We estimate that this 'ring rain' drains an amount of water products that could fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool from Saturn's rings in half an hour," said planetary scientist James O'Donoghue of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

"From this alone, the entire ring system will be gone in 300 million years, but add to this the Cassini-spacecraft measured ring-material detected falling into Saturn's equator, and the rings have less than 100 million years to live.

"This is relatively short, compared to Saturn's age of over 4 billion years."

Hints of ring rain were first spotted in some curious phenomena observed by the Voyager probes. They detected some strange changes in Saturn's ionosphere, density variations in the rings themselves, and three dark bands circling Saturn at mid-northern latitudes.

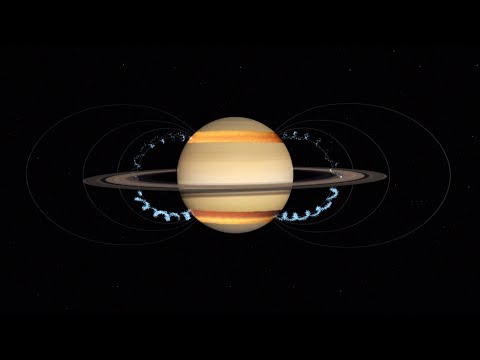

Initially, these things were thought to be unrelated. But then a 1986 paper proposed that those dark bands were being caused by ice particles from Saturn's rings, charged by the Sun or plasma fields and pulled down the planet's magnetic field lines.

When they come into contact with Saturn's upper atmosphere, these ice particles vaporise, and this influx of water clears the haze, which then shows up as dark bands.

As for the ionosphere changes, those are also tied to the ring rain. The charged particles interact chemically with Saturn's ionosphere, resulting in long-life trihydrogen cations that glow in infrared. The team was able to see these glowing infrared bands on Saturn, and match it up to the estimated rainfall rate.

The research has also provided evidence to solve another mystery: when and how Saturn's rings appeared. Did they form with the planet, or did they arrive later?

Evidence obtained by Cassini pointed to old, old rings, when the Solar System was still forming. But prior to that, scientists had thought that the rings were perhaps only 100 million years old, possibly created by a collision between a moon and a comet, or between Saturn's moons (it has many), which resulted in debris captured in rings by the planet's gravity.

According to the research team, the rate of ring decay is more consistent with the earlier hypothesis - that is, an age of about 100 million years - because that's how long it would take the planet's C ring to become as thin as it is, assuming it was once as dense as the B ring.

"We are lucky to be around to see Saturn's ring system, which appears to be in the middle of its lifetime," O'Donoghue said.

But never fear - there are other ring systems in the Solar System. Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune all have rings, and they may stick around for a bit longer. Uranus' rings are thought to be around 600 million years old at a maximum, which means they could have very different dynamics from Saturn's.

Neptune is also thought to have very young rings, but there's a big question mark standing over Jupiter. Maybe they're all reaching the end of their lifespan after all.

"If rings are temporary," O'Donoghue said, "perhaps we just missed out on seeing giant ring systems of Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune."

Now that would have been something to see.

The team's research has been published in the journal Icarus.