Researchers in the US have developed a new drug that can be delivered directly into the eye via an eye dropper to shrink down and dissolve cataracts - the leading cause of blindness in humans.

While the effects have yet to be tested on humans, the team from the University of California, San Diego hopes to replicate the findings in clinical trials and offer an alternative to the only treatment that's currently available to cataract patients - painful and often prohibitively expensive surgery.

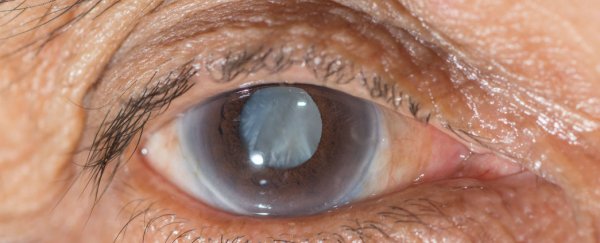

Affecting tens of millions of people worldwide, cataracts cause the lens of the eye to become progressively cloudy, and when left untreated, can lead to total blindness. This occurs when the structure of the crystallin proteins that make up the lens in our eyes deteriorates, causing the damaged or disorganised proteins to clump and form a milky blue or brown layer. While cataracts cannot spread from one eye to the other, they can occur independently in both eyes.

Scientists aren't entirely sure what causes cataracts, but most cases are related to age, with the US National Eye Institute reporting that by the age of 80, more than half of all Americans either have a cataract, or have had cataract surgery. While unpleasant, the surgical procedure to remove a cataract is very simple and safe, but many communities in developing countries and regional areas do not have access to the money or facilities to perform it, which means blindness is inevitable for the vast majority of patients.

According to the Fred Hollows Foundation, an estimated 32.4 million people around the world today are blind, and 90 percent of them live in developing countries. More than half of these cases were caused by cataracts, which means having an eye drop as an alternative to surgery would make an incredible difference.

The new drug is based on a naturally-occurring steroid called lanosterol. The idea to test the effectiveness of lanosterol on cataracts came to the researchers when they became aware of two children in China who had inherited a congenital form of cataract, which had never affected their parents. The researchers discovered that these siblings shared a mutation that stopped the production of lanosterol, which their parents lacked.

So if the parents were producing lanosterol and didn't get cataracts, but their children weren't producing lanosterol and did get cataracts, the researchers proposed that the steroid might halt the defective crystallin proteins from clumping together and forming cataracts in the non-congenital form of the disease.

They tested their lanosterol-based eye drops in three types of experiments. They worked with human lens in the lab and saw a decrease in cataract size. They then tested the effects on rabbits, and according to Hanae Armitage at Science Mag, after six days, all but two of their 13 patients had gone from having severe cataracts to mild cataracts or no cataracts at all. Finally, they tested the eye drops on dogs with naturally occurring cataracts. Just like the human lens in the lab and the rabbits, the dogs responded positively to the drug, with severe cataracts shrinking away to nothing, or almost nothing.

The results have been published in Nature.

"This is a really comprehensive and compelling paper - the strongest I've seen of its kind in a decade," molecular biologist Jonathan King from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) told Armitage. While not affiliated with this study, King has been involved in cataract research for the past 15 years. "They discovered the phenomena and then followed with all of the experiments that you should do - that's as biologically relevant as you can get."

The next step is for the researchers to figure out exactly how the lanosterol-based eye drops are eliciting this response from the cataract proteins, and to progress their research to human trials.