Scientists have found that the cells responsible for spreading cancer around the bodies of mice have a big weakness - they need certain fats to fuel their growth.

Now a team of researchers has shown that by blocking these cells from absorbing fat they can actually stop cancer from metastasising in mice - and they're hoping the results might help them do the same in humans.

Metastasis is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the world, but until now, scientists have struggled to understand exactly how and why cancer cells go through the energy-intensive process of splitting off, travelling through the bloodstream, and taking root somewhere else in the body.

In the past, it was assumed that sugar was cancer's main fuel source, but a study earlier this year suggested that we'd been looking at metastasis entirely wrong - what if fat was actually driving the spread of cancer?

Now a new study adds more weight to this hypothesis.

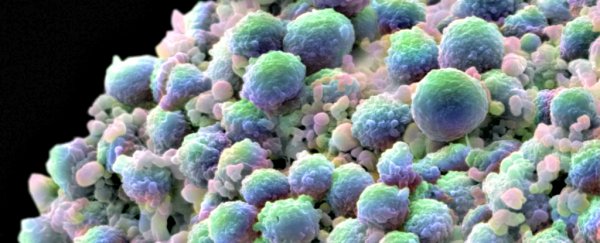

A team of researchers identified the cells responsible for the spread of oral cancer in mice, and showed that they rely on fatty acids - including palmitic acid, a major component of common food additive palm oil - to spread around the body.

They figured this out after noticing that many of the metastasising cells expressed high levels of a receptor protein called CD36, which helps cells absorb lipids.

High expression of CD36 has also been linked to poor medical outcomes in cancer patients, so the team decided to see what would happen if the receptor was blocked.

Incredibly, the researchers showed that when they blocked CD36 expression in a range of human cancer cells, they were able to stop the cancer from spreading altogether in mice - although it didn't stop primary tumours from forming.

"We hypothesise that metastatic cells rely so much on the availability of certain fatty acids, that they cannot cope without them," lead researcher Salvador Aznar Benitah told Research Gate.

"However, we still do not know the precise mechanism of why blocking CD36 results in such a strong effect on metastasis."

While the team still has more work to do, their results so far show that the approach might also work after cancer has metastasised.

In mice, blocking CD36 with antibodies eradicated metastatic tumours 15 percent of the time, and the remaining tumours that had spread shrunk by at least 80 percent.

The study also showed that mice fed high-fat diet had more and larger tumours in their lymph nodes and lungs - which is a sign of them spreading - compared to mice on normal diets.

To be clear, this research has only been done on human cancer cells in mice, so there's no guarantee the same thing will work in human patients.

And at this stage, no one is recommending anyone cut fats from their diets to avoid cancer spread - especially seeing as many cancer patients need high-energy diets in order to stay healthy.

But the team is working on creating antibodies that work against CD36 in humans, and hope to test them in clinical trials within the next five years.

"This is an important and exciting first step," said Benitah. "Now that we have been able to identify these cells responsible for metastasis, we can study their behaviour in much more detail."

"Also, it opens the possibility of a new anti-metastatic therapy based on blocking the ability of these cells to uptake fatty acids," he added.

We're looking forward to seeing what comes of this research, because while we're closing in on many revolutionary new treatments for cancer, being able to stop it from spreading in the first place would be incredible.

The research has been published in Nature.