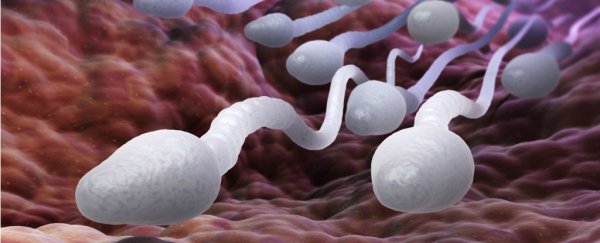

Sperm has been having a tough time lately. The concentration per ejaculate is getting lower, scientists have created an artificial version that could one day replace it, and to make matters worse, common household products might affect the quality of the little guys.

Unfortunately this new study just adds to the bad news, discovering a completely new sperm structure, which may be partially responsible for everything from infertility to miscarriages and birth defects.

If you remember back to high school biology, you might recall that the centriole is a structure in the cytoplasm of a cell that helps with cell division.

What the researchers, from the University of Toledo, found, was that there's a second extra centriole in sperm, which the researchers call an 'atypical' centriole, and this guy has a number of weird properties.

To start with, although they have the same function, these two centrioles look very different.

"Abnormalities in the formation and function of the atypical centriole may be the root of infertility of unknown cause in couples who have no treatment options available to them," Tomer Avidor-Reiss, from Toledo's Department of Biological Sciences, said in a press release.

"It also may have a role in early pregnancy loss and embryo development defects."

You need two centrioles to make the working centrosome, and until now it was thought that the sperm provided one centriole to the egg, and then duplicated itself.

"Since the mother's egg does not provide centrioles, and the father's sperm possesses only one recognisable centriole, we wanted to know where the second centriole in zygotes comes from," Avidor-Reiss said.

"It was overlooked in the past because it's completely different from the known centriole in terms of structure and protein composition."

But, instead of being duplicated the second centriole actually is there all along, but it looked weird enough that scientists didn't notice.

The atypical centriole contains a small set of the full complement of proteins, which allows it to create a full and functional centriole after fertilisation.

But does this one structure cause all of those fertility issues? Well, we can't get too ahead of ourselves just yet.

This extra centriole gives scientists a new avenue to explore when other, known problems can't explain infertility, miscarriages and birth defects - but it definitely doesn't mean this atypical centriole is always to blame.

"We are working with the Urology Department at The University of Toledo Medical Center to study the clinical implications of the atypical centriole to figure out if it's associated with infertility and what kind of infertility," Avidor-Reiss said.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.