Getting enough toxic material to the right place in your body for it to kill tumours – while not damaging anything else – has always required thinking outside of the box.

Wrapping sperm cells in an iron suit and then guiding them to a target using magnetic fields could be one innovative way to deliver drugs to parts of the female reproductive system affected by cancer.

Researchers from the Institute for Integrative Nanosciences and the Chemnitz University of Technology in Germany have found a way to harness a process already well adapted to navigating the harsh environments of the vagina, cervix, uterus, and fallopian tubes to treat conditions such as gynaecological cancer, endometriosis, and pelvic inflammatory diseases.

Delivering drugs in effective doses to the right site without damaging healthy cells is one of the main challenges in research on cancer treatment.

Packing the drugs in tiny bubbles, such as in microscopic vessels called liposomes, helps make them more soluble and helps protect the body from the toxic contents as they're carried through the body.

Unfortunately there are still a bunch of other problems to solve, including dilution of the packages as they spread through the body and getting the drug inside the target cells.

Nature does offer a solution in the form of cells that can propel themselves in a specific direction thanks to a 'motorised' whip called a flagellum, while sniffing out chemical hotspots to zero in on.

Thanks to this, many species of bacteria would be perfectly suited to navigating pathways through the body either in search of a chemically labelled beacon or under some sort of external control, if not for the unfortunate fact that they'd probably be gobbled up by our immune system long before they succeeded in their mission.

Sperm could also offer a better solution, particularly for conditions like those inside the female reproductive tract.

Not only are they already suited to navigating such an environment, their membranes offer a perfect way to package drugs to avoid dilution, immune responses, or break-down from the body's enzymes.

Since they're also suited to fusing with ova during fertilisation, the sperm's membranes also offer a convenient way to deliver drugs into the cells of the target tissue.

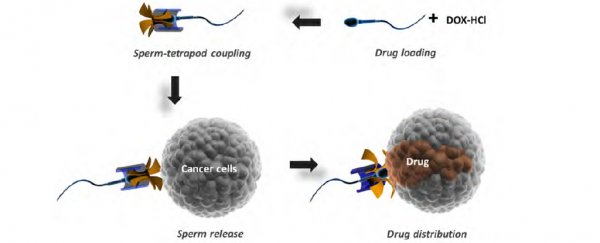

The researchers tested their idea by soaking bovine sperm cells in a form of chemotherapy medication called doxorubicin, one commonly used to treat gynaecological cancers by interrupting their building of certain large protein molecules, something mature sperm no longer worry about.

To drive the sperm in the right direction, the team use a form of 3D printing called nanolithography to create a tiny harness that was coated with a thin layer of iron.

This iron suit responded to magnetic fields arranged in such a way to guide the sperm's marathon swim in a specific direction.

Four flexible arms were built into the front of the sperm's harness, designed to bend as they rammed into a cell and release the sperm from its tiny guidance collar.

With their tiny drug smugglers dressed for success and loaded to the cytoplasm with doxorubicin, the researchers put them through a series of experiments to test their motility, guidance, and ability to deliver the drugs into lab-grown cancer cells called HeLa.

While the harness slowed their speed by nearly half and the chemotherapy drug had a small impact on the distance they could travel, they still managed to move on command and deliver the drugs inside the cancer cells, at least in a petri dish.

The research has been released on the pre-publish website arXiv.org, where it's openly available for other interested researchers to discuss before the researchers submit it for peer review.

Cervical cancer was responsible for the death of 266,000 women around the globe in 2012, which on its own accounts for just 7.5 percent of all cancer deaths among women.

"Although there are still some challenges to overcome before this system can be applied in in vivo environments (e.g. imaging, biodegradation of the synthetic part, multiple sperms carrying and delivery, and improved control of sperm release), sperm-hybrid systems may be envisioned to be applied in in situ cancer diagnosis and treatment in the near future," the researchers conclude in their research.

While there is still plenty of work to be done to determine how effective this delivery method might actually be, and if there are any side-effects from the discarded harnesses, this is an impressive first step into a treatment that could help save the lives of thousands of women around the world who are diagnosed with gynaecological cancer every year.