The South Atlantic island of Tristan da Cunha is proud of its status as the most remote civilisation in the world, but that isolation comes with plenty of challenges. Now the 266-strong community is getting a major redesign to help it become more self-sufficient.

Modernised buildings, a wind farm, and a waste-to-energy incinerator are all incoming, with an emphasis on getting the locals to develop the kinds of technologies that they're comfortable using.

The new vision for the island comes from UK-based architecture firm Brock Carmichael, which was awarded the job of redeveloping Tristan da Cunha's settlements through an international design competition held by the Royal Institute of British Architects.

The winner was picked by representatives of Tristan da Cunha, with the island's head of government, Alex Mitham, saying the Brock Carmichael plans showed a "practical approach and an in-depth understanding" of life in the South Atlantic.

The island, which is part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension, and Tristan da Cunha, might have its own Royal Mail postcode - TDCU 1ZZ - but its extreme remoteness means this is no ordinary town planning brief.

When the nearest landmass is more than 1,609 km (1,000 miles) in any direction - and passenger ships dock at the island only eight times a year - relying on outsiders to fix problems or repair buildings isn't really an option.

Which is why the new plans focus on construction ideas and sustainability projects that the locals can manage themselves.

"Over a course of time key people would be trained in any areas of expertise required to deliver these design proposals and acquire the knowledge and skills that can be passed down to generations to come," says chief architect Martin Watson.

So, in the case of rebuilding government offices and homes, rather than using imported and untested materials, Brock Carmichael has suggested that the residents stick to their traditional building techniques, but add an extra layer of enveloping insulation (made in part from local sheep wool) to keep the warmth in and reduce energy usage.

The architects want to optimise every part of the development process, from the importing of building materials to the island to cutting down on leftover waste and recycling. Local basaltic rock, beach sand, and seaweed are going to be used wherever possible.

Communal kitchen gardens and a hydroelectric plant are on the table too, though Brock Carmichael is waiting for its architects to visit and inspect Tristan da Cunha in the summer of 2017 before filling in too much detail on their initial designs.

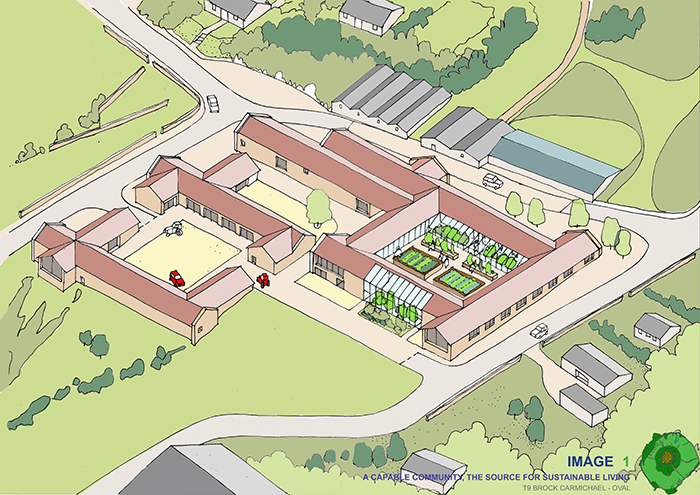

Sketches of the plans for Tristan da Cunha. Credit: Brock Carmichael

Sketches of the plans for Tristan da Cunha. Credit: Brock Carmichael

But the architects don't have the final say: only if the initiative is viable and self-sustaining, and has the support of local residents and officials, will it be added to the final project plans.

And the locals have an ambitious goal that they want the redesign to meet, with an aim of producing 30 to 40 percent of their own energy within the next five years.

Such close involvement with the redevelopment project should in itself give the Tristan da Cunha villagers extra skills they can use elsewhere, as well as a strong sense of belonging in their redesigned home, Martin Watson says.

While the island might sound like your kind of remote utopia, don't get too attached: outsiders aren't allowed to settle or buy land on Tristan da Cunha, though they're welcome to visit. Most jobs revolve around lobster farming, managed through a South African company.

Another thing to bear in mind is that this intriguing patch of rocky land also sits on an active volcano, and has to deal with the threat of both tropical storms and earthquakes. Fortunately, all of these factors will be addressed as much as they can in the plans being developed.

It's early days yet, as Tristan da Cunha's transformation could take years to achieve, but we can't wait to see how it turns out.