A new discovery has potentially doubled the number of supermassive black holes that astronomers thought existed in our Universe.

Supermassive black holes were traditionally thought to be at the centre of all big galaxies, such as our own Milky Way. Now, a new study suggests they could also be at the centre of all dwarf galaxies, too.

It all started three years ago, when astronomers from the University of Utah discovered a supermassive black hole lurking in an ultra-compact dwarf galaxy.

Since then, it's remained the smallest known galaxy to house a giant black hole, but now the same team has found two more dwarf galaxies with supermassive black holes, suggesting that perhaps the pairing isn't as uncommon as initially predicted.

With an estimated 7 trillion dwarf galaxies in the visible Universe, this might make supermassive black holes far more prolific than astronomers thought.

Even more impressive, the findings of the recent study reveal that, despite their size, these dwarf galaxies contain black holes even larger than our own.

"It's pretty amazing when you really think about it," says lead researcher Chris Ahn.

"These ultra-compact dwarfs are around 0.1 percent the size of the Milky Way, yet they host supermassive black holes that are bigger than the black hole at the centre of our own galaxy."

If you need a little perspective for just how mind-meltingly massive black holes can get, check out the video below:

The research also answers some ongoing questions about dwarf galaxies themselves.

When astronomers first discovered ultra-compact dwarf galaxies in the 1990s, they noticed something strange - the dwarf galaxies had more mass than their stars could account for.

The new study suggests that supermassive black holes are responsible for this extra mass - and it could also shed light on how galaxies were created in the first place.

"We still don't fully understand how galaxies form and evolve over time," says Ahn. "These objects can tell us how galaxies merge and collide."

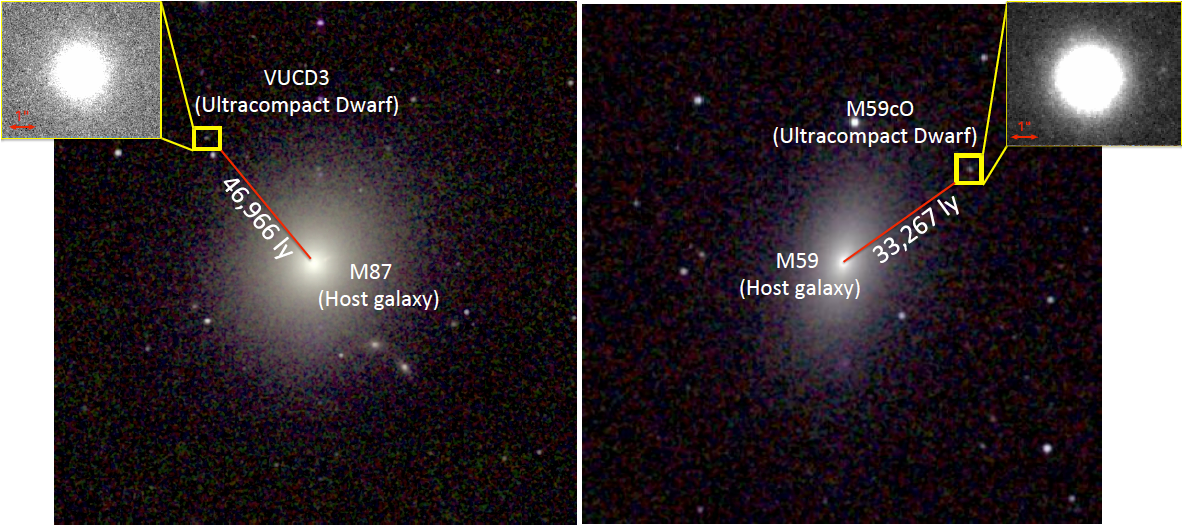

Using adaptive optics, a technique that allows galaxies to be brought into finer focus, researchers measured the two ultra-compact dwarf galaxies, named VUCD3 and M59cO.

The findings revealed that VUCD3's black hole was 13 percent of the galaxy's total mass, and M59cO's black hole was 18 percent of its total mass.

NASA/Space Telescope Science Institute

NASA/Space Telescope Science Institute

Those readings are way larger than the black hole in the Milky Way, which makes up a little less than .01 percent of our galaxy's total mass.

The findings lay to rest the idea that these dwarf galaxies are just massive star clusters, composed of hundreds of thousands of stars all created at the same time.

Instead, the study supports the idea that these dwarf galaxies were swallowed up and ripped apart by the gravity of larger galaxies.

"We know that galaxies merge and combine all the time - that's how galaxies evolve," says one of the researchers, Anil Seth. "Our Milky Way is eating up galaxies as we speak."

"Our general picture of how galaxies form is that little galaxies merge to form big galaxies," he added. "But we have a really incomplete picture of that. The ultra-compact dwarf galaxies provide us a longer timeline to be able to look at what's happened in the past."

Dwarf galaxies might be small, but they could hold the answer to some very large questions.

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.