If the dating of a number of East African artefacts turns out to be correct, the emergence of our genus might have been given a boost when hominids literally gave tools an edge.

Systematically flaked stones buried in sediment dated from 2.58 to 2.61 million years ago were uncovered at an Ethiopian dig site back in 2012, and a new analysis reveals they just might beat the current record-holder for the world's oldest intentionally sharpened tool.

Arizona State University geologist Christopher Campisano made the find at a site called Bokol Dora 1 in the Lower Awash Valley. It's already a region famous for palaeontological remains of early humans such as the 3.18-million-year-old Australopithecus known affectionately as Lucy.

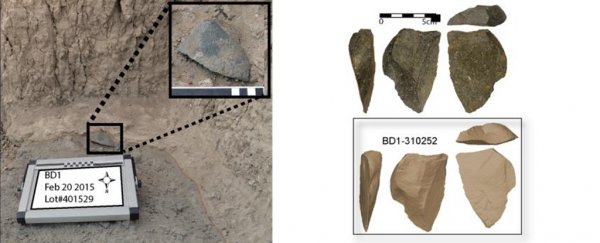

"At first we found several artefacts lying on the surface, but we didn't know what sediments they were coming from," says Campisano.

"But when I peered over the edge of a small cliff, I saw rocks sticking out from the mudstone face. I scaled up from the bottom using my rock hammer and found two nice stone tools starting to weather out."

Over the following two dig seasons, some 300 stones and several hundred associated fossils were removed from the interface of two distinct layers of sediment.

The site is relatively close to the place where a 2.78-million-year-old fossilised jawbone of an early member of the Homo genus was uncovered by Campisano and his colleagues in 2013.

Whether the tools are closely connected with this particular ancient group of hominids isn't yet clear, but it's possible they could represent a key moment in human evolution.

The use of stones as a tool among primates dates back far longer than a few million years. Shared ancestors of humans and other apes have probably been bashing away at food items for many millions of years.

Selecting for the best hammer is one thing, but turning a choice bit of rock into a precise cutting implement is something else altogether.

Right now, the consensus pick for the world's oldest edged tools are another set of artefacts found in the Awash Valley, amid what's known as the Gona River drainage.

Those were securely dated to a time between 2.55 to 2.58 million years ago and represent the oldest examples of what's known as Oldowan technology.

Their discovery not only set a boundary for the dawn of tool creation among humans, but hinted at long periods of technological stagnation, with few changes being seen in the basic Oldowan design over time.

With so few examples of ancient artefact available, though, it's hard to map the steps taken between finding a hammer and designing a knife.

Circumstantial evidence for early tools has certainly arisen over the years. Scraps of animal bones dated to around 3.4 million years ago bear slice marks that seem to be intentional.

Flaked stones found in Kenya in 2011 also point to some kind of percussive tool creation around 3.3 million years ago. These so-called Lomekwian artefacts predate our own genus by half a million years, suggesting relatives of Lucy might have been responsible.

The Bokol Dora 1 discovery would reset the horizon for cutting tools closer to the emergence of Homo, marking a radical shift from crafting simple bludgeoning implements to the deft handiwork needed to precisely remove flakes, and make something capable of hacking and slicing.

Putting all of the evidence together, we might speculate that features characteristic of our own branch of the hominin tree developed in line with tools that helped early humans to not only access more nutrients, but whittle big morsels of food into smaller ones.

Not only might this have helped ancient humans to tuck into a few extra mouthfuls of meat, but it might have allowed for smaller teeth and jaw muscles, turning a strong, robust head into our more gracile one capable of finer forms of communication.

If we were hoping for clues on how Lucy's hammer might have slowly transformed into a hatchet, though, it seems we're going to have to keep digging.

"We expected to see some indication of an evolution from the Lomekwian to these earliest Oldowan tools," says anthropologist Will Archer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig.

"Yet when we looked closely at the patterns, there was very little connection to what is known from older archaeological sites or to the tools modern primates are making."

That could mean we're yet to find 'stepping stones' between the technologies. Or, it's also possible there are no such incremental steps, and each form of tool was invented from scratch by distinct populations of early humans.

It pays to be cautious when it comes to making these kinds of claims, though, given ancient stone artefacts don't come with easy-to-read stickers labelling their creation date. Not everybody is convinced that the tools were dropped exactly where they were found.

Further analysis could help, but for now, we can tentatively add the discovery to the handful of ancient artefacts that tell an intriguing story of the dawn of human technology.

This research was published in PNAS.