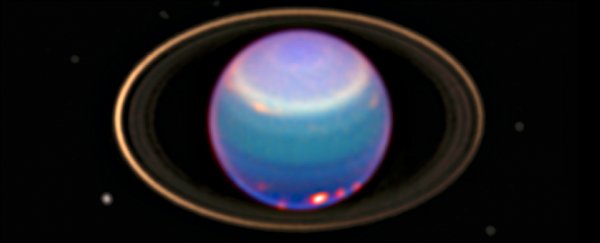

Researchers have re-examined data captured by the Voyager 2 spacecraft back in 1986, and think they've found evidence of two never-before-seen moons hidden in the rings of Uranus.

Uranus, the third largest planet in our Solar System, already has 27 moons that we know of - but these two new ones appear to orbit the planet more closely than any of its other natural satellites, and are causing wavy patterns in its closest rings.

Although Saturn is the most famous ringed planet orbiting our Sun, it's not the only one, with the three other gas giants - Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune - all having their own ring systems.

But we haven't had much opportunity to study Uranus, seeing as it's almost 20 times further from the Sun than Earth is, and much of the information we have on it came from Voyager 2's flyby 30 years ago.

Now a duo of planetary scientists from the University of Idaho have re-examined this data to show that there's something strange going on in two of Uranus' 13 rings, called Alpha and Beta.

These rings display a previously unnoticed wavy pattern, suggesting that they're being pulled at by two tiny moons.

"These patterns may be wakes from small moonlets orbiting exterior to these rings," the researchers write in their paper on the pre-print site arXiv.org.

So why didn't Voyager 2 see these moons as it zipped past?

The researchers suggest these moons are so tiny, and also so dark, that they would have blended into the background for the spacecraft. Being "dark" means they barely reflect any light, as is the case with most of the moons in the area, and also Uranus's dark rings.

But the two Idaho researchers, Rob Chancia and Matthew Hedman, have crunched the numbers, and suggest that the pattern they detected in the Alpha and Beta rings are similar to those caused by the pull of some of Uranus's other moons, such as Cordelia and Ophelia.

They predict that, if these two new moons exist, they would only measure between 4 and 14 km (2 to 9 miles) across.

For now, this discovery is far from confirmed, and the researchers are still in the process of publishing in a peer-reviewed journal. But you can read their full report on arXiv.org now, and the team is getting ready to inspect Uranus with the Hubble Space Telescope in order to get more information.

Mark Showalter from the SETI Institute in California, who has previously discovered moons around Uranus, but wasn't involved in the study, told Ken Croswell over at New Scientist that the existence of the two new moons is "certainly a very plausible possibility".

He also said that Hubble is the "best bet" for finding these new Uranian satellites, but if that fails, maybe it would be time for Uranus to get its own orbiter mission - which we're totally on board with.

It's been a good year for our Solar System, with a new dwarf planet discovered last week, and another one back in May, as well as a moon hiding at the back of our Solar System earlier this year.

The better we get at peering out into space, the more crowded our neck of the galaxy gets, and we love it. The more curiosities to understand, the better.