Given the sole purpose of kitchen sponges is to, you know, absorb stuff, we probably shouldn't be surprised by how mind-bogglingly filthy these things can get – and yet here we are.

Scientists in Germany have conducted what they say is the world's first comprehensive study of contamination in used kitchen sponges, and it backs up we already feared: these soggy, porous 'cleaning products' are positively teeming with living bacteria.

Researchers led by Furtwangen University ran genetic sequencing on samples from 14 different used kitchen sponges and ended up finding 362 different types of bacteria happily lounging within all that comfortable, springy foam.

Fortunately for you and me, the majority of this bacteria was in fact not harmful – but some of it was.

"What surprised us was that five of the ten [types] which we most commonly found, belong to the so-called risk group 2 (RG2)," says lead researcher, microbiologist Markus Egert, "which means they are potential pathogens."

These included Acinetobacter johnsonii, Moraxella osloensis, and Chryseobacterium hominis – which the researchers say can lead to infections – plus Acinetobacter pittii and Acinetobacter ursingii.

Of these, bacteria in the family Moraxellaceae was the most dominant kind found, backing up previous research on sponges.

Since Moraxellaceae is also common on human skin, the researchers speculate that it might be people touching sponges that introduces this particular contamination.

What makes sponges – which the team call "the biggest reservoirs of active bacteria in the whole house" – so problematic isn't just their damp, porous structure, which provides an optimal breeding ground for microbes.

It's also that we insist on then wiping these dense bug-ridden colonies over other, potentially clean surfaces in the house, including bench tops, appliances, and kitchen sinks.

"Kitchen sponges not only act as [a] reservoir of microorganisms, but also as disseminators over domestic surfaces, which can lead to cross–contamination of hands and food, which is considered a main cause of food–borne disease outbreaks," the authors write in their paper.

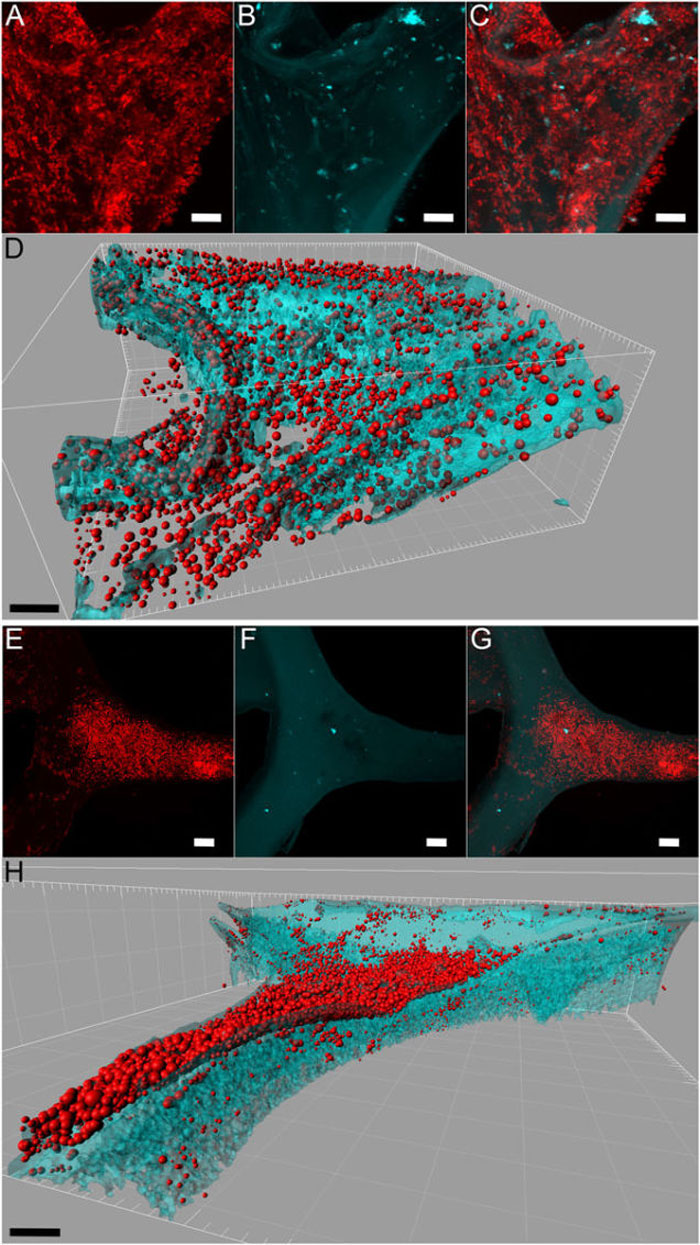

In addition to the sequencing, the team was able to visualise the presence of bacteria in the samples in 3D using a technique called fluorescence in situ hybridisation coupled with confocal laser scanning microscopy (FISH–CLSM).

The visualisations reveal how the large surface area, moist foam, and scattered food matter within the sponge provide the perfect, incubating habitat for bacteria.

So much so, in fact, that it's almost hard to differentiate where the sponge (blue) stops and the bugs (red) start:

Cardinale et al

Cardinale et al

"Sometimes the bacteria achieved a concentration of more than five times 1010 cells per cubic centimetre," says Egert.

"Those are concentrations which one would normally only find in faecal samples. And levels which should never be reached in a kitchen."

Most surprising of all was the finding that, whatever you do, you shouldn't try to clean or sterilise your sponge, because doing so only encourages the hardiest bugs to overcome your efforts.

While we might think that microwaving sponges, dousing them in boiling water, or running them through the dishwasher should sanitise the foam, the team found that regularly cleaned sponges were about as bug-ridden as uncleaned ones – and could even increase the abundance of Moraxella and Chryseobacterium.

"Presumably, resistant bacteria survive the sanitation process and rapidly re–colonise the released niches until reaching a similar abundance as before the treatment," the team writes.

"This effect resembles the effect of an antibiotic therapy on the gut microbiota and might promote the establishment of higher shares of RG2-related species in the kitchen sponges."

Okay, so if we can't clean these filthy things, how long should we use them for? One week, the researchers say, before promptly replacing them.

That's not going to be great for the environment – although sponges are mostly made from polyurethane, which we just might have a way of breaking down.

Still, a week really isn't very long. After all, when was the last time you replaced yours?

Farewell, trusty (if not so sterile) sponge, we hardly knew you.

The findings are reported in Scientific Reports.