The high seas of the dinosaur era were teeming with a plethora of squids, a new study has found.

Using a new technique for analyzing fossils locked away in chunks of rock, paleontologists in Japan and Germany have discovered a huge number of fossilized cephalopod beaks in a 100-million-year-old rock.

That included 263 squid samples – and among these samples lurked 40 species of ancient squids that scientists had never seen before.

It's a finding that reveals just how numerous squids were in the Cretaceous ocean, even though their fossilized remains are rarely found.

Related: This Ancient Vampire Squid Is Destined to Clutch Its Last Prey Forever

"In both number and size, these ancient squids clearly prevailed the seas," says paleobiologist Shin Ikegami of Hokkaido University, first author of the research.

"Their body sizes were as large as fish and even bigger than the ammonites we found alongside them. This shows us that squids were thriving as the most abundant swimmers in the ancient ocean."

To make a fossil, you generally need body parts that take a long time to decay, so that the long, often rigorous fossilization process has time to take place without destroying the remains. Most fossils are bone, tooth, shell, and claw; soft body parts require exceptional fossilization circumstances.

Squids consist mostly of soft body parts. The one exception is their hard, chitinous beak. Squid beaks that manage to survive on the fossil record of Earth's history would be vital for understanding how these fascinating cephalopods – a group of animals that includes octopuses, nautiluses, and cuttlefish – emerged and evolved over their 500 million years on this Earth.

Prior to this study, only one single fossilized squid beak had been found. Many small marine fossils, however, are deposited in jumbled assemblages that are difficult to extract and study.

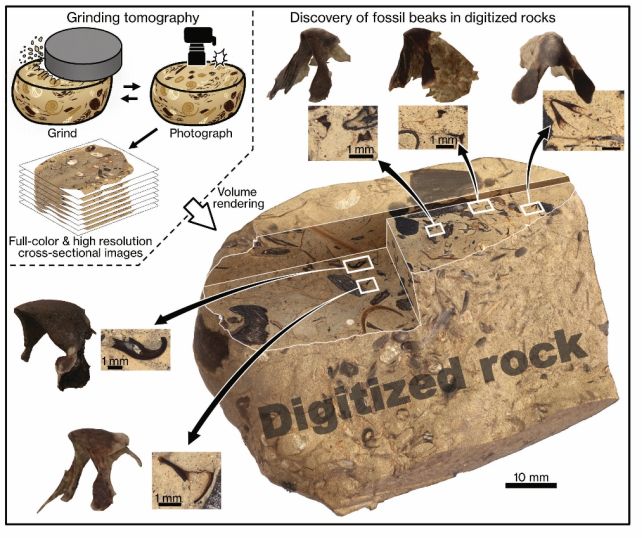

To discover their remarkable beak assemblage, the researchers turned to a technique called grinding tomography. Basically, scientists gradually sand away a rock sample, thin layer by thin layer, imaging each layer in high resolution as they go.

The sample itself is destroyed. But the resulting images can then be compiled digitally to reveal the interior contents of the rock in three dimensions – including highly detailed, 3D reconstructions of the fossils therein, which usually would only be accessible in two-dimensional slices.

Ikegami and his colleagues used this technique to reconstruct a piece of fossil-riddled rock dating back to around 100 million years ago. Inside was a dense assemblage of animal remnants, including some 1,000 cephalopod beaks, among which the squid beaks emerged.

These beaks were tiny and thin, ranging in length from 1.23 to 19.32 millimeters, with an average length of 3.87 millimeters, about 6 percent of the size of the only previously known fossil squid beak. The minimum thickness of these beaks was always less than 10 micrometers, the scientists found.

"These results show that numerous squid beaks are hidden as millimeter-scaled microfossils and explain why they have been overlooked in previous studies," the scientists write in their paper.

Based on these results, the researchers inferred that the Cretaceous squid biomass would have far exceeded the biomasses of fishes and ammonites, and that squid diversification had absolutely exploded by around 100 million years ago.

This is in stark contrast to the previous assumption that squids only began to thrive on Earth after the mass extinction that brought about the end of the dinosaur age, some 66 million years ago.

"These findings change everything we thought we knew about marine ecosystems in the past," says paleontologist Yasuhiro Iba of Hokkaido University. "Squids were probably the pioneers of fast and intelligent swimmers that dominate the modern ocean."

The research has been published in Science.