We can only guess at the kind of day one iguana-like lizard was having 100 million years ago in what is now Myanmar. All we have to go on is its tiny back leg and some slime mould it shook loose, perhaps in an effort to escape death by tree sap.

The fossilised remnants of the tragic event have been analysed in detail in previous studies. Attention has now moved from the lizard's foot to the few slimy filaments, which make the amber a truly unique specimen.

A team of researchers from the US, Germany, and Finland have taken a close look at the exquisitely preserved spore masses of what is taxonomically referred to as a myxomycete, but more commonly known as a slime mould.

Slime moulds have captured our attention thanks largely to their talent for rapidly adapting to changes in their environment on a biochemical level - essentially 'learning' and 'memorising' in ways that help it to avoid threats or find food.

There's no doubt they're fascinating organisms, but the creeping tendrils of their web-like ichor are just half of their life story. Maybe not even that.

For one thing, they're not moulds. Usually they're not even slimy. Most of the time, they live a simple life as a single-celled microbe belonging to the group of amoebozoans.

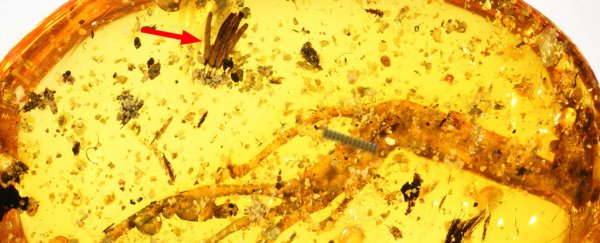

Because their soft bodies are soft and their livelihoods microscopic, preserved examples of ancient myxomycetes are hard to come by. In fact, this is the only known example from the entire age of the dinosaurs, captured during the Cretaceous in what is today the country of Myanmar.

(Alexander Schmidt, University of Göttingen/Scientific Reports)

(Alexander Schmidt, University of Göttingen/Scientific Reports)

Similar to the reptilian limb preserved in pristine condition in its chamber of amber, the neatly detailed specimen of myxomycete represents just a small part of a bigger body.

But it is a significant part – the handful of 2 millimetre long fruiting bodies, or sporocarps (shown below larger than life), allows taxonomists to compare the ancient specimen with modern slime moulds.

(Alexander Schmidt, University of Göttingen/Scientific Reports)

(Alexander Schmidt, University of Göttingen/Scientific Reports)

The closest match is with a genus called Stemonitis, a common slime mould that grows on most continents, clinging to rotting wood.

In fact, it's fairer to say the specimen isn't just comparable with the modern genus. Their characteristics are close to identical, indicating just how little the physiology of these organisms has changed over tens of millions of years.

"The fossil provides unique insights into the longevity of the ecological adaptations of myxomycetes," says palaeontologist Alexander Schmidt from the University of Göttingen.

When nature strikes a winning formula, it doesn't tend to deviate from it very far. Sending tiny spores on air currents to propagate works just as well now as it did then, providing little incentive for this particular lineage of slime moulds to try something new.

"We interpret this as evidence of strong environmental selection," says University of Helsinki microbiologist Jouko Rikkinen.

"It seems that slime moulds that spread very small spores using the wind had an advantage."

What makes it an even more amazing find is the fact fruiting bodies of a myxomycetes are short lived. Their preservation was truly a chance event. There are just two other similar examples, which are roughly 35 to 40 million years old.

Just what happened on that fateful day is left up to our imagination, but it's not hard to picture the scene.

"The fragile fruiting bodies were most likely torn from the tree bark by a lizard, which was also caught in the sticky tree resin, and finally embedded in it together with the reptile," suggests Rikkinen.

It was one bad day for that poor little tropical lizard. But we can thank it for the small but crucial role it played in preserving a piece of myxomycete history, showing just how timeless these weird but amazing organisms are.

This research was published in Scientific Reports.