Think of a major city in the United States. Chances are, its land is slowly sinking.

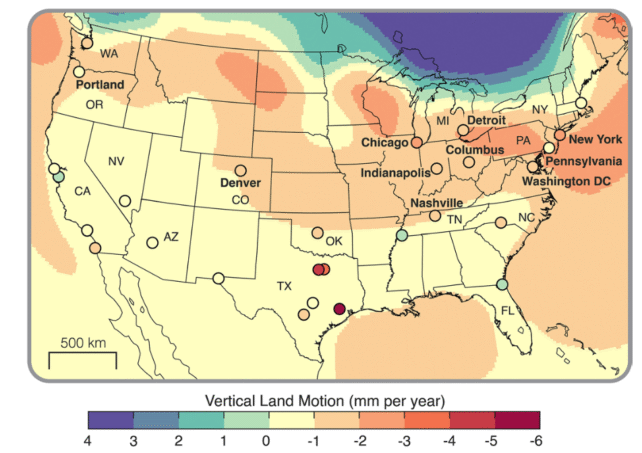

A new satellite radar study has now found evidence that the nation's 28 most populous cities are all buckling under the pressure of urbanization, drought, or rising sea levels, to varying extents.

In every city analyzed, at least 20 percent of the urban land sank at least somewhat between 2015 and 2021. What's more, in 25 out of all 28 major cities, at least 65 percent of the land looks to be sinking.

From the coast to the interior, researchers estimate these sinking urban hubs hold the weight of nearly 34 million people – about 12 percent of the total US population.

While the cities aren't at risk of immediate collapse, these are concerning downward trends that need to be addressed.

"Subsidence is a pernicious, highly localized, and often overlooked problem in comparison to global sea level rise, but it's a major factor that explains why water levels are rising in many parts of the eastern US," said geophysicist Leonard Ohenhen in 2024.

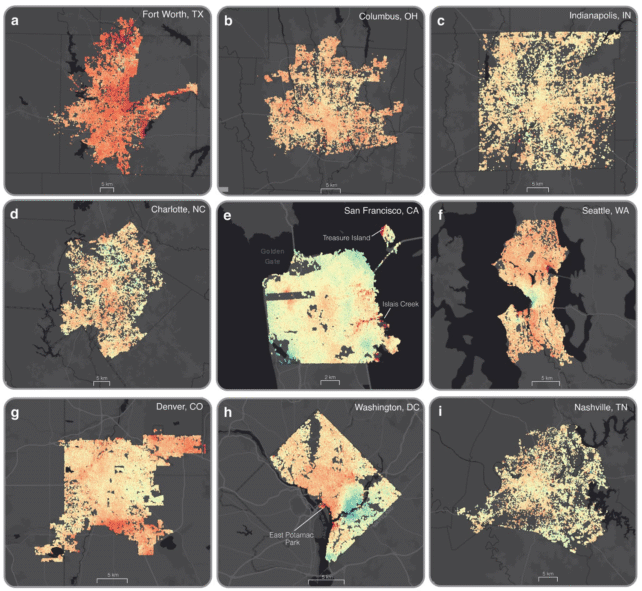

Ohenhen has been analyzing subsidence rates in the US for the past year, and in a new study he and his team show that urban areas with 98 percent or more sinking land include Chicago, Dallas, Columbus, Detroit, Fort Worth, Denver, New York, Indianapolis, Houston, and Charlotte.

Meanwhile, the cities with particularly rapid rates of sinking, greater than 2 millimeters per year, include New York, Chicago, Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, Columbia, Seattle, and Denver.

In Texas, cities like Fort Worth, Dallas, and Houston are experiencing some of the fastest subsidence rates in the nation, with an average exceeding 4 mm a year, the new study finds.

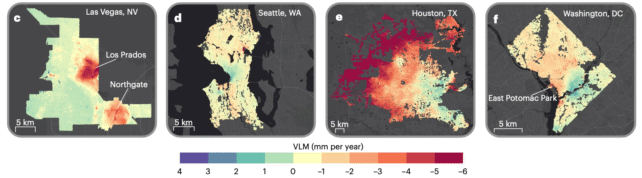

Most other cities have only localized zones where the land is sinking faster than 5 mm per year, like San Francisco's Treasure Island and areas around Islais Creek.

Scientists generally agree that subsidence rates of greater than 5 mm a year pose a significant concern to cities, but even in places with lower rates, infrastructure damage is a risk, especially if the land from area to area is not sinking evenly.

If that's the case, as it is in New York, Las Vegas, and Washington, DC, it can cause cracking and destabilization for roads, buildings, and bridges. If the ground sinks far enough, it can also lead to flooding risks.

The authors of the current study, who hail from a variety of institutions across the US, estimate that more than 29,000 buildings in major American cities are currently located in areas with high and very high risk of damage.

"The latent nature of this risk means that infrastructure can be silently compromised over time with damage only becoming evident when it is severe or potentially catastrophic," explains geophysicist Manoochehr Shirzaei from Virginia Tech.

"This risk is often exacerbated in rapidly expanding urban centers."

Houston is the fastest-sinking city out of all 28 US cities investigated by satellites. Just over 40 percent of its land is subsiding faster than 5 mm per year, largely because of long-term groundwater mining and oil and gas extraction, and 12 percent is subsiding faster than 10 mm per year.

In their models, researchers found a strong correlation between the vertical deformation of cities, like Houston, and modern changes in groundwater levels.

This suggests that by easing up on groundwater extraction, cities could potentially slow their sinking lands. But the solution for each city is complicated and depends on its size, geology, and specific threats.

In coastal cities dealing with rising sea levels, for instance, adaptations could include protection from intruding saltwater and storm surges, or retreat, Shirzaei and colleagues suggest.

Meanwhile, cities like New Orleans that face flooding risks may require raised land or improved drainage systems. Urban centers at risk of uneven cracking could retrofit or introduce infrastructure to better withstand moving foundations.

"Our long-range goal is to map all of the world's coastlines using this technique," Shirzaei said in 2024.

"We know that planners in several US cities are already using our data to make our coastlines more resilient, and we want cities all over the world to be able to do be able to do the same."

The study was published in Nature Cities.