Three skeletons uncovered in a rock shelter adorned with red pigment rock art reveal burial rituals of early humans who followed well-trodden paths through Indonesia's Lesser Sunda Islands, albeit thousands of years apart.

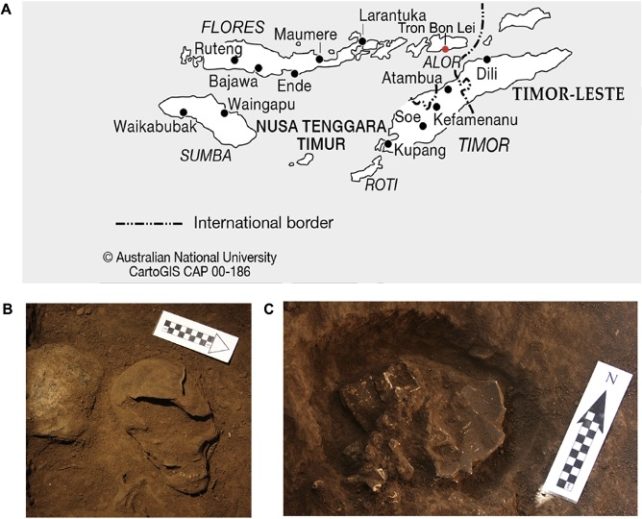

Aside from deepening our understanding of the evolution and diversification of burial practices, the finds – from Alor Island in southeast Indonesia – enrich past discoveries that previously provided some clues about patterns of migration of early humans making their way southward.

"Burials are a unique cultural manifestation to investigate waves of migration through the terminal Pleistocene to the Holocene period in Southeast Asia," says archaeologist Sofia Samper-Carro of the Australian National University.

From the positioning and treatment of bodies to the presence or absence of ornamental grave goods, Southeast Asian burial sites "offer a panoply of social expressions related to the deposition of the deceased," Samper-Carro and colleagues write in their paper.

Past research casts South East Asia as a melting pot of ancient humans who crossed paths and (possibly) interbred in a landscape that was vastly different during the Pleistocene, the last ice age.

Traversing islands, oceans, and now-drowned land bridges took skilled mariners further southward until they crossed through Wallacea and voyaged to Australia, which, at the time, was attached to New Guinea as part of a much larger land mass called Sahul.

With so many possible routes and scant archaeological evidence, it has been tricky to pinpoint which way and when people made those fateful migrations.

In previous work, Samper-Carro and colleagues started piecing together a more complete picture of modern humans moving through the islands of southeast Indonesia, describing what are among the earliest human remains in the area.

Comparative analyses of the original excavations suggested there were four waves of migrations through the Lesser Sunda Islands – which include Flores – where researchers found the pint-sized Homo floresiensis.

"Our first excavations in 2014 revealed fish hooks and a human skull that was more than 12,000 years old," says Samper-Carro of the initial discovery at the Tron Bon Lei rock shelters that also yielded cranial fragments dated to 17,000 years old.

But there was more to this story. When the researchers returned four years later to further excavate the burial site, widening it to the southeast, they unearthed two more bodies buried in different positions, one on top of the other.

The first skeleton, dated to roughly 7,500 years old, laid in an oval-shaped grave littered with shell flakes and framed by ochre-stained rocks. Beneath it was a 10,000-year-old skeleton interred in a seated position in a circular grave stacked with Turbo shells at the base.

Below that was the body to which the original 12,000-year-old skull belonged. The woman was relatively small, the researchers inferred, which could reflect a somewhat genetically isolated population on the islands.

Also of note was a shellfish hook lying on its left side, placed at the neck of the almost complete female skeleton. Researchers used this adornment to confirm the age of the remains.

All told, they suspect the burials illustrate shifts and continuities in social behaviors of modern humans, humans who appear to have repeatedly used the rock shelter on Alor Island as a burial site over thousands of years.

"The three quite unusual and interesting burials show different mortuary practices, which might relate to recent discoveries of multiple migratory routes through the islands of Wallacea from thousands of years ago," Samper-Carro explains.

Some features of these burials do, however, show similarities to other graves found across mainland and southeast Asian islands, which could suggest early humans exchanged cultural information as they migrated. But it could also be that these burial practices emerged locally.

Genetic analyses of the remains are now underway, along with dietary studies. Researchers expect that genetic profiling could reveal evidence of different migratory groups that gave rise to modern humans currently living on the islands.

"These future efforts will provide us deeper insights to interpret the lifeways of communities inhabiting Mainland and Island Southeast Asia during the Pleistocene and Holocene," the team concludes.

The research was published in PLOS ONE.