Dutch archaeologists on Wednesday revealed an around 4,000-year-old religious site – dubbed the "Stonehenge of the Netherlands" in the country's media – which included a burial mound serving as a solar calendar.

The burial mound, which contained the remains of some 60 men, women and children had several passages through which the Sun directly shone on the longest and shortest days of the year.

"What a spectacular archaeological discovery! Archaeologists have found a 4,000-year-old religious sanctuary on an industrial site," the town of Tiel said on its Facebook page.

"This is the first time a site like this has been discovered in the Netherlands," it added in a statement.

Diggings around the so-called "open-air sanctuary" started in 2017 in the small village about 50 kilometers (31 miles) southeast of Utrecht, with the results made public on Wednesday.

Studying a difference in clay composition and color, the scientists located three burial mounds on the excavations, a few kilometers from the banks of the Waal river.

The main mound is about 20 meters (65 feet) in diameter with its passages lined up to serve as a solar calendar.

"People used this calendar to determine important moments including festival and harvest days," the archaeologists said.

"This hill reminded one of Stonehenge, the well-known mysterious prehistoric monument in Britain, where this phenomenon also occurs," NOS, the Dutch national broadcaster, added.

Scientists also discovered two other smaller mounds. The three mounds were used as burial sites for about 800 years, the archaeologists said.

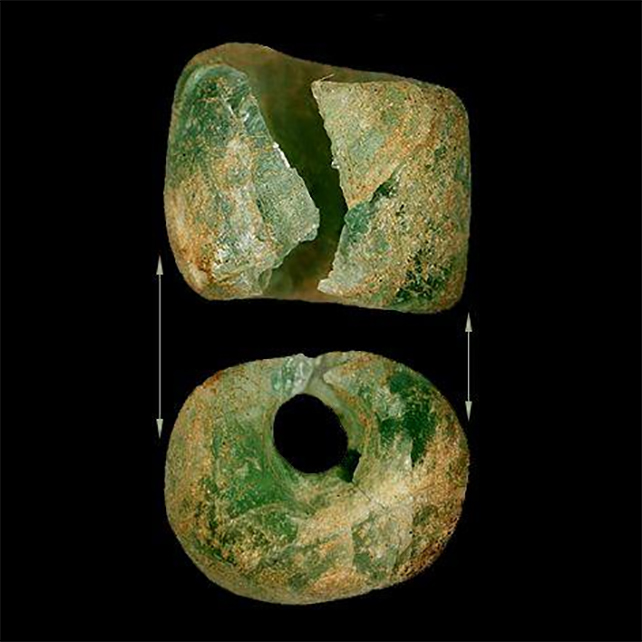

They made another fascinating discovery: a single glass bead inside a grave, which after analysis was shown to have originated in Mesopotamia, today's Iraq.

"This bead travelled a distance of some 5,000 kilometers, four millennia ago," said chief researcher Cristian van der Linde.

"Glass was not made here, so the bead must have been a spectacular item as for people then it was an unknown material," added Stijn Arnoldussen, professor at the University of Groningen.

He told the NOS that the Mesopotamian bead may have been around for a long time before eventually ending up in the area around Tiel, called the Betuwe in Dutch.

"Things were already being exchanged in those times. The bead may have been above ground for hundreds of years before it reached Tiel, but of course, it didn't have to be," Arnoldussen said.