Far beneath the wavetops, down into the dark ocean depths, a rarely seen crustacean makes its home.

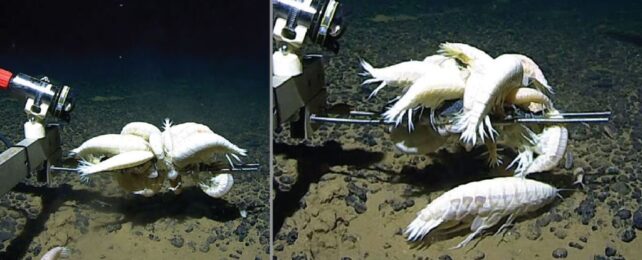

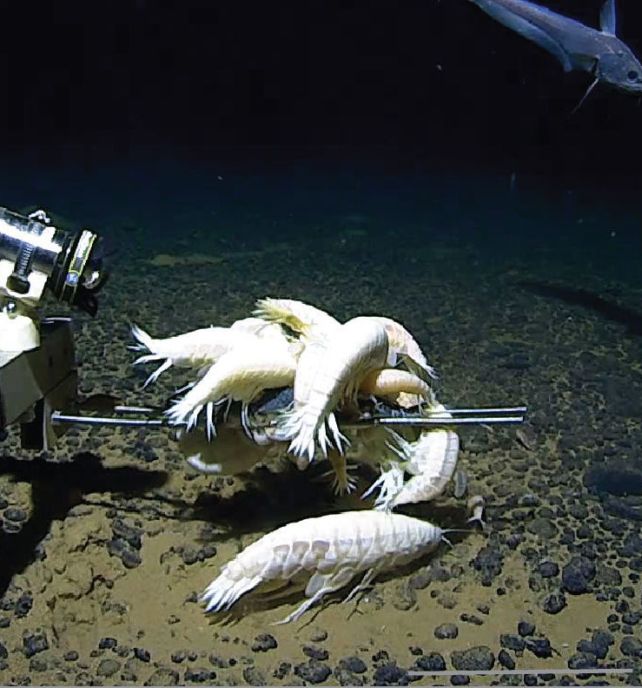

It's called Alicella gigantea, and it's the largest known species of amphipod, a shrimp-like species that is usually less than the size of your fingertip. By this measure, A. gigantea is a gargantuan: it can reach up to 34 centimeters (13.4 inches), as far as we have been able to verify.

We thought that these creatures were pretty rare; very few have ever been spotted. New research, however, suggests that A. gigantea might be widespread, occupying 59 percent of the world's oceans – its apparent scarcity more a product of our own observation bias than representative of any reality.

It's a finding that underscores just how little we know about what dwells in the darkness of the oceanic abyss.

"Historically, it has been sampled or observed infrequently relative to other deep-sea amphipods, which suggested low population densities," says marine molecular biologist Paige Maroni of the University of Western Australia.

"And, because it was not often found, little was known about the demography, genetic variation and population dynamics with only seven studies published on DNA sequence data."

The problem with finding A. gigantea is that it lives deep under the ocean, in the abyssal and hadal zones below depths of 3,000 meters (9,843 feet). By around 1,000 meters down, sunlight is no longer able to penetrate the water; it gets very, very cold, and very, very dark. In addition, with the weight of all that water bearing down, pressures are crushing.

Its inhospitality to us land-dwellers plays a major role in why humanity's exploration of the deep sea is minuscule. So it's probably unsurprising that we have an extremely incomplete understanding of what's living down there.

To find out, Maroni and her colleagues conducted a survey of encounters with the species. They compiled 195 records of A. gigantea, from 75 different sites in the deep sea in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, from depths of 3,890 to 8,931 meters. They also collected specimens for themselves to sequence their genomes, and found them in fracture zones in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

The genomes revealed genetic similarities between populations found in different seas, suggesting that the animals are more connected than we would have thought. The information suggests that A. gigantea can be found thriving on the floor of the deep sea in their depth range, which the researchers estimate represents 59 percent of Earth's total seafloor.

Previous studies on deep-sea amphipods suggest that the lack of pigmentation of A. gigantea – quite strange for an amphipod, which are usually hued along the red spectrum – may be because it doesn't have any major predators. That would certainly facilitate a widespread distribution.

"As exploration of the deep-sea increases to depths beyond most conventional sampling, there is an ever-growing body of evidence to show that the world's largest deep-sea crustacean is far from rare," Maroni says.

The research has been published in Royal Society Open Science.