Scientists at Harvard University are proposing a fundamental change in the way we consider psychedelics and their therapeutic potential.

Using mouse models and human cells, the team of neuroscientists has demonstrated that hallucinogens hold the potential to reshape communication between brain cells and the immune system.

"Our study underscores how psychedelics can do more than just change perception; they can help dial down inflammation and reset brain-immune interactions," explains neuroimmunologist Michael Wheeler from Harvard and Brigham and Women's Hospital.

"This could reshape how we think about treatment for inflammatory disorders and conditions like anxiety and depression."

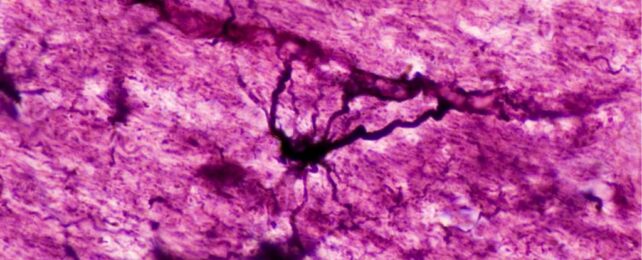

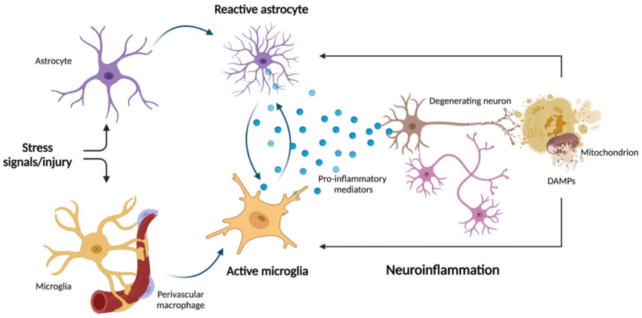

Emerging research suggests that inflammation in the brain may increase the risk of major psychiatric disorders, and specific cells called astrocytes play a key role in that immune response.

Astrocytes are the most common cell in the central nervous system, and recent studies on mice suggest that when these neural entities experience strong and prolonged activation, it can increase inflammation in the brain and lead to anxiety and stress responses.

While much is still unknown about psychedelics and the impact they have on human health, some studies suggest that hallucinogens like LSD are potent anti-inflammatory agents, which can regulate astrocyte activity.

To explore that idea further, Wheeler and his colleagues turned to mice that had experienced short-term stress for 7 days and chronic stress for 18 days.

Using genome analysis and behavioral tests, the team found that mouse brains exposed to small bouts of stress are generally resilient. In mice experiencing stress for seven days, astrocytes in the brain's amygdala – crucial for emotional control – were linked to fewer stress-induced fear responses.

This resilience was linked to the expression of a specific receptor on astrocytes, called EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor), which seems to reduce 'crosstalk' between neurons and immune cells.

When a mouse experienced chronic and overwhelming stress for 18 days, however, their EGFR expression was reduced, and this triggered a cascade of inflammatory responses and fear behaviors.

"What is fascinating is that psychedelic compounds can reverse this entire process," says Wheeler.

When he and his colleagues administered psilocybin or MDMA to mice with poor EGFR function, they found a reduction in inflammatory cells surrounding the brain and reduced fear behaviors.

To explore whether the same effect is possible in our own species, the team turned to human cells. Not only did the Harvard researchers find similar signals of stress in our own brain cells, they also analyzed human gene expression data from people with major depressive disorder and found altered EGFR signaling.

Further experiments are needed to explore how psychedelics impact EGFR expression and what this does to inflammation in the brain, but the evidence that psychedelics can reshape immune responses in the central nervous system is compelling.

Inflammation is tied to a whole host of neurodegenerative diseases and mood disorders, and these findings highlight "potential direct and indirect mechanisms by which psychedelics influence physiological responses to chronic stress and neuroimmune interactions."

"We're not saying that psychedelics are a cure-all for inflammatory diseases or any other health condition," explains Wheeler.

"But we do see evidence that psychedelics have some tissue-specific benefits and that learning more about them could open up entirely new possibilities for treatments."

The study was published in Nature.