Earth's surface is mostly deep ocean, but a new study reveals just how little we have glimpsed of the floor of our planet's largest ecosystem.

Researchers at the non-profit Ocean Discovery League, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and Boston University have now calculated how much of the seafloor we have imaged so far based on publicly available data.

In all the 67 years humans have been recording deep-sea dives, it seems our species has visually explored between 0.0006 and 0.001 percent of the deep seafloor.

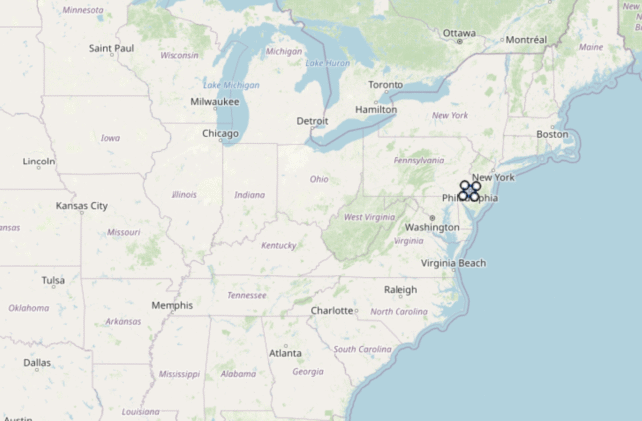

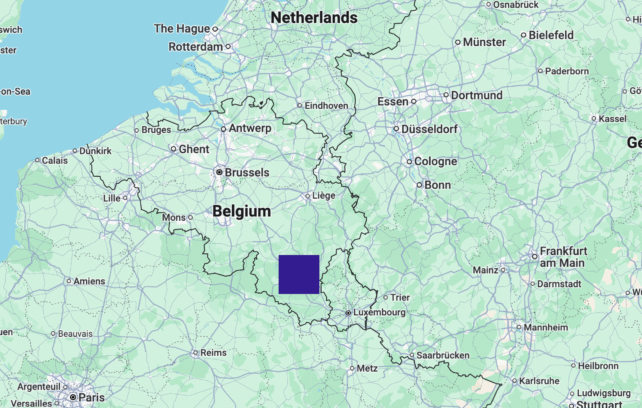

That upper estimate represents just 3,823 square kilometers (1,476 square miles) of territory, slightly larger than the smallest US state, Rhode Island, or about a tenth the size of Belgium.

Like the deep seafloor itself, sometimes you have to see a concept to really believe it – and that goes for numbers, too.

Lead author and deep-sea explorer Katherine Bell and her team have put together a few handy visual comparisons for their estimates.

The image below, for instance, shows just how much of the seafloor we have glimpsed when combined together and overlaid on a partial map of the United States.

For those who are more familiar with Europe, this image shows the same amount of deep seafloor but laid across Belgium.

"We have visual records of a minuscule percentage of the deep seafloor, an ecosystem encompassing 66 percent of the surface of planet Earth," writes the team of data crunchers.

To make matters murkier, nearly 30 percent of those visual explorations involve black-and-white, low-resolution, still images, taken before 1980.

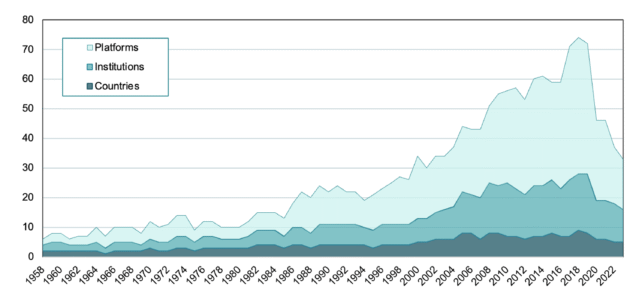

To settle on their estimates, Bell and colleagues aggregated more than 43,000 records of submergence activities greater than or equal to 200 meters (656 feet). These were either conducted within the coastlines of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) or the high seas.

While this dataset does not include private oil and gas explorations, even if estimates are off by a full order of magnitude, that's 0.01 percent of the seafloor that has been visually imaged.

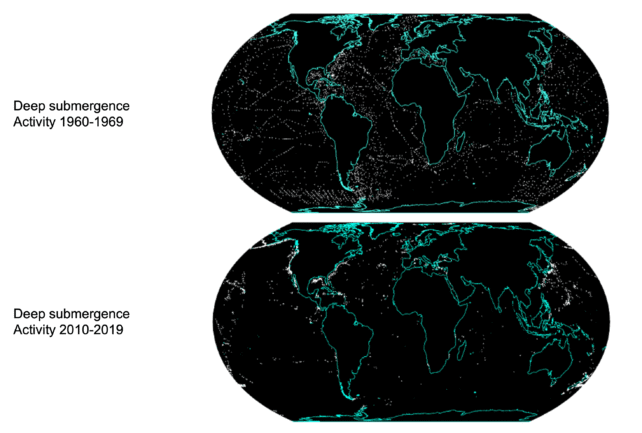

From the 1960s to the 2010s, the team found that the number of deep-sea dives increased by fourfold. That shows great progress; however, over time, these explorations started to cluster near coastlines and shallower depths.

In the 1960s, nearly 60 percent of all dives were deeper than 2,000 meters, but four decades later, only a quarter went that deep.

When nearly three-quarters of the ocean lies between 2,000 and 6,000 meters below the waves, that's a significant skew.

And there are other biases impacting our understanding of the deep ocean, too. In the 1960s, half of all dive activities took place in what is now the high seas, but by the 2010s that fell to just 15 percent.

Most modern deep dives are now conducted in EEZs. In fact, of the more than 35,000 dives conducted within 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers) of coastal states, over 70 percent were within the waters of only three high-income countries: the US, Japan, and New Zealand.

That makes more sense when you consider that 97 percent of all dives since 1958 were conducted by just five countries: the US, Japan, New Zealand, France, and Germany.

In 1961, American attorney and journalist John F. Kennedy, Jr. told Congress that "knowledge of the oceans is more than a matter of curiosity. Our very survival may hinge upon it."

Seven decades later, those words still ring true.

"As we face accelerated threats to the deep ocean – from climate change to potential mining and resource exploitation – this limited exploration of such a vast region becomes a critical problem for both science and policy," says Bell, founder and President of the Ocean Discovery League.

"We need a much better understanding of the deep ocean's ecosystems and processes to make informed decisions about resource management and conservation."

Even if we increase our deep-sea explorations by more than a thousand platforms worldwide, Bell and colleagues predict it would take 100,000 years or so to visualize Earth's entire seafloor.

So don't hold your breath.

"These estimates illustrate that we need a fundamental change

in how we explore and study the global deep ocean," the authors conclude.

The study was published in Science Advances.