There's nothing quite like getting lost in an excellent book (or an article from your favorite science news site). But we know surprisingly little about what actually goes on in the brain as it transforms strings of squiggly symbols on our pages and screens into entire worlds inside our heads.

"Despite a great deal of neuroscientific research on the representation of language, little is known about the organization of language in the human brain," neuroscientist Sabrina Turker, from Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Germany, pointed out back in 2023.

"Much of what we do know comes from single studies with small numbers of subjects and has not been confirmed in follow-up studies."

To find out more about the very specific aspect of language known as reading, Turker and her colleagues from Max Planck have conducted a meta-analysis that brings together the results of 163 experiments that involved brain scans – either fMRI or PET – from a total of 3,031 adults.

These experiments spanned all manner of reading tasks in various alphabetic languages, from individual letters to full texts, silent and read aloud, real words and nonsense words.

"What is typically considered 'reading' in the literature and by non-linguists, is usually semantic access [i.e. making meaning from written words], whereas what all included tasks here have in common is phonological processing [ie the brain's ability to organize sounds and generate meaning from them]," the authors write.

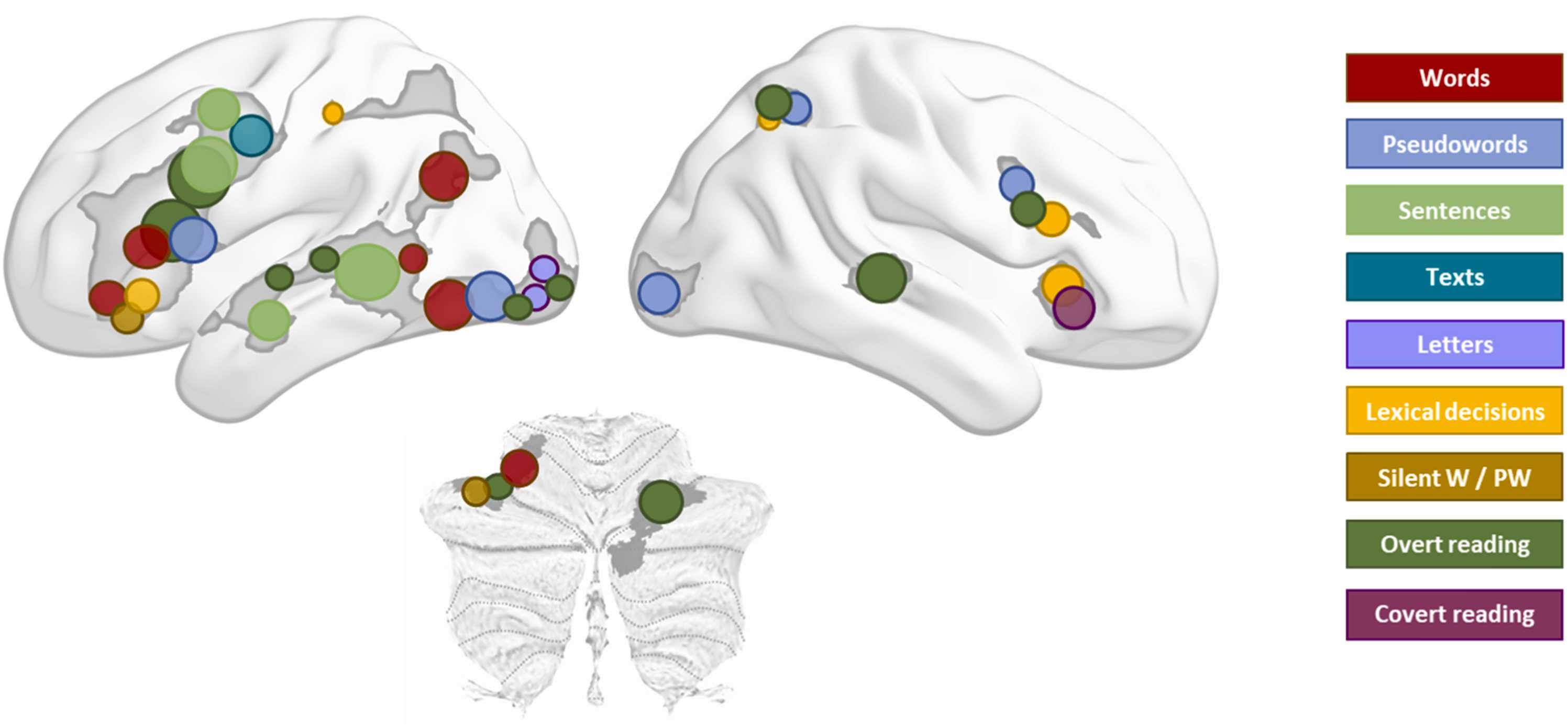

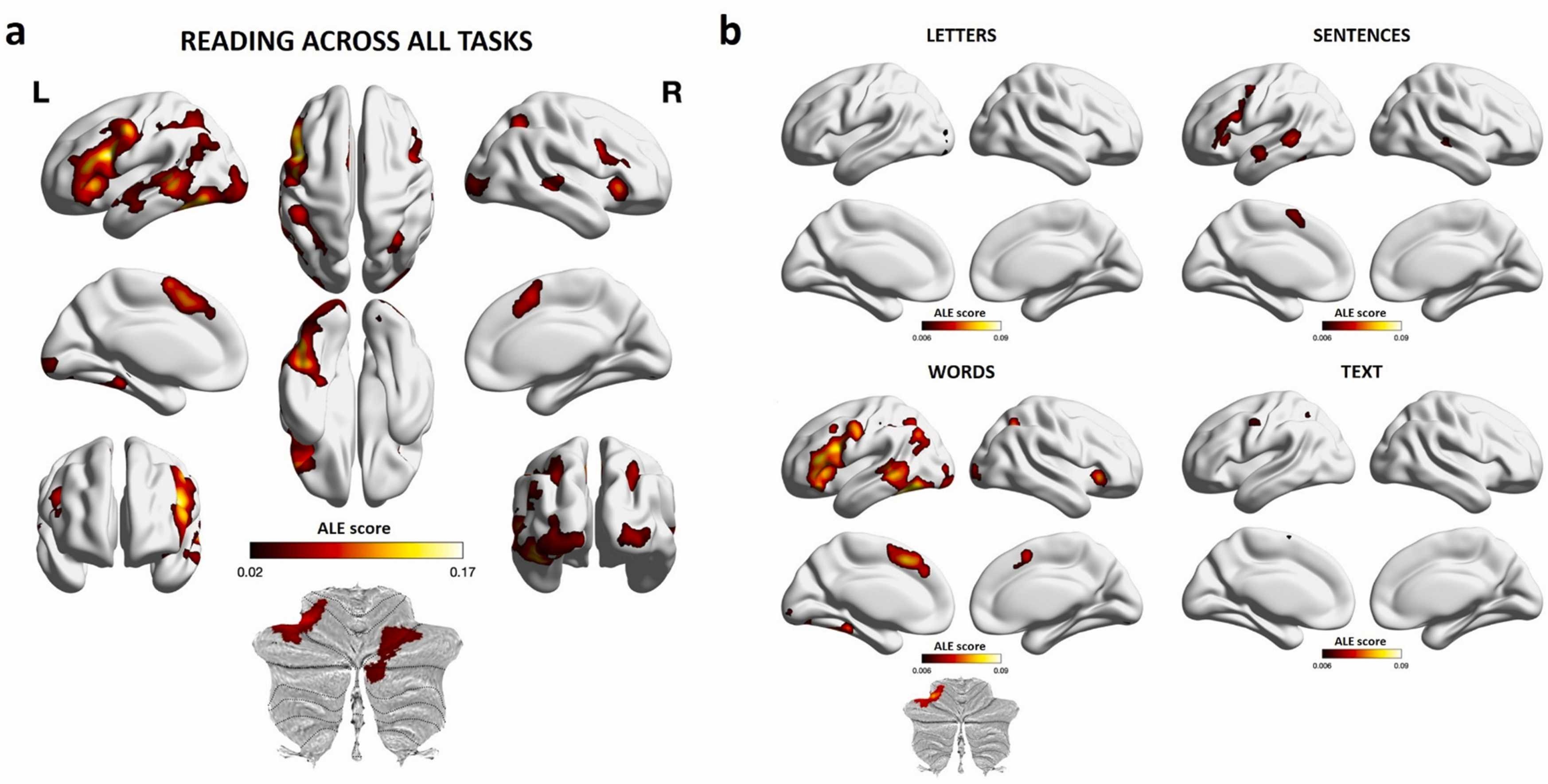

The left hemisphere of the brain is known to be the center of language processing, so it's not too surprising that all kinds of reading, whether of individual letters, sentences, or entire texts, seemed to light up this side of the brain.

"We found high processing specificity for letter, word, sentence, and text reading exclusively in left-hemispheric areas," the team writes.

Letter and text reading particularly engaged the left visual and motor areas, while word and sentence reading put to work various classical language clusters within the left hemisphere, the team says.

Previously, neuroscience has somewhat ignored the role of the cerebellum in language. Hints that this may be an oversight came from a study, also led by Turker and published in 2023, which showed the cerebellum is involved not only in processing sounds, but also in making meaning – both crucial components of language.

Now, it looks like it's busy when you're reading, too. The new study found the right cerebellum in particular was active in all kinds of reading tasks. Certain areas of the right cerebellum appeared far more active when reading out loud, which suggests they are vital in our ability to translate written word into speech.

The left cerebellum, meanwhile, seemed particularly engaged during word reading (as opposed to letter, sentence, or text reading).

"While the left cerebellum seems to show stronger semantic [meaning-making] involvement during reading, the right cerebellum contributed mainly to overall reading processes, potentially due to its role in speech production," the authors report.

They also compared data on out-loud and silent reading tasks. Reading out loud was more likely to activate auditory and motor regions, while silent reading relied on regions that coordinate multiple cognitive demands.

Silent reading of words (or pseudo-words) activated the left orbitofrontal, cerebellar, and temporal cortices more consistently than when reading required interpretation to decode implicit meaning. This implicit reading mode tended to recruit both sides of the inferior frontal and insular regions of the brain.

The authors say their study "extends our understanding of the neural architecture underlying reading, corroborates findings from neurostimulation studies and can provide valuable neural insight into reading models."

This research is published in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews.