The Aztec Empire once hosted an expansive trade network that brought volcanic glass to its capital from right across Mesoamerica, coast to coast.

The largest compositional study of obsidian artifacts found in the ancient Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan has now revealed the far-flung influence of the Mexica culture – the largest and most powerful faction of the Aztec Alliance.

The 788 precious obsidian objects analyzed include weapons, urns, earrings, pendants, scepters, and decorated human skulls. They appear to have been sourced from across the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, even from the lands of rival governments.

The discovery speaks to the commercial prowess of the Aztec Empire at its peak.

"This work not only highlights the Mexica Empire's reach and complexity but also demonstrates how the archaeological sciences can be leveraged to study ancient objects and what they can tell us about past cultural practices," says anthropologist Jason Nesbitt from Tulane University in the US.

The Aztec Empire is known to have used obsidian ubiquitously. This volcanic glass is harder than ordinary steel, fractures smoothly into an edge sharper than a razor blade, has a mirror-like quality when polished, and comes in a variety of beautiful colors.

Researchers have found obsidian objects at Aztec sites in abundance, but rarely has previous research brought together such a large collection for analysis of the mineral's origins.

"This kind of compositional analysis allows us to trace how imperial expansion, political alliances, and trade networks evolved over time," explains lead author and anthropologist Diego Matadamas-Gomora from Tulane.

Working with Mexico's Templo Mayor Project and the National Institute of Anthropology and History, Matadamas-Gomora and colleagues have laid out a timeline and a map for hundreds of obsidian objects found in the Aztec's late-capital – which now sits beneath the historic center of Mexico City.

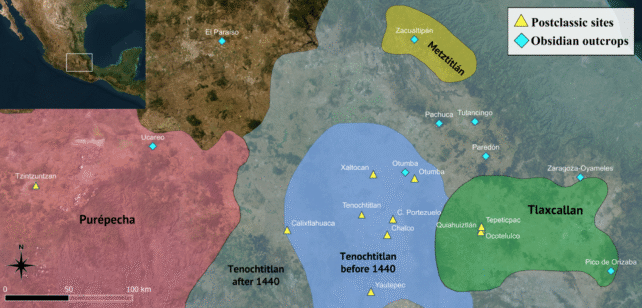

Nearly 90 percent of the haul can be traced to Sierra de Pachuca, about 94 kilometers (58 miles) northeast of Tenochtitlan – a region that is known for its green and golden volcanic glass.

The rest of the obsidian objects are derived from seven different locations, some of which sit far outside the ancient lands once dominated by the Mexica between 1375 and 1520 CE.

In the early phases of the Mexica culture, before the Aztec Alliance formed, Tenochtitlan's obsidian was sourced mostly from nearby Pachuca. But after the consolidation of the Empire around 1430 CE, obsidian from rival polities seems to have been brought to the capital in greater numbers.

For instance, the authors traced some obsidian blades and flakes to the region of Ucareo, located 173 kilometers northwest. This area was dominated by the Purépecha Empire, who spoke a different language to the Aztecs.

"It is well known that the Mexica had quarries and workshops in Sierra de Pachuca to get direct access to this type of obsidian," write the authors of the analysis.

"However, even if the Mexica exploited and transported obsidian in large quantities from Pachuca to Tenochtitlan, this situation did not limit their access to obsidian from several other deposits, some of them beyond their political borders."

Most of the obsidian artifacts analyzed by the anthropologists were everyday items, used as weapons or for construction.

These objects would have probably been bought by city residents in Tenochtitlan's great market. Historical documents suggest merchants from various regions in Central America would gather here to sell their goods.

"The presence of at least seven sources of obsidian indicates that the Mexica expanded their commercial interactions during this period," writes the team.

Ritual objects made of obsidian, however, were rarely made from 'foreign' volcanic glass. These sacred relics were usually sourced from the nearby Sierra de Pachuca, probably because of the unique green colors.

By studying the origins of Aztec obsidian, researchers hope to further map the movement of goods across Mesoamerica, following in the steps of a long-lost empire.

The study was published in PNAS.