Being pregnant in the Viking Age was surely no picnic, but this experience has been largely ignored, in part because there are very few records to go by.

A new analysis of Viking art and literature, led by archaeologist Marianne Hem Eriksen from the University of Leicester, lays out the patchy but fascinating history of pregnancy in the Viking Age.

While archaeologists have uncovered thousands of Viking burials, there are very few mother-infant, and especially few infant, burials from this period, though birth- and pregnancy-related deaths would have been high. This suggests infants and mothers were not buried together, or that perhaps infants were not given the same rites.

In literature and art, the authors note, pregnant women were often left out of the story, but there are two very famous depictions in the sagas, and neither of them are particularly passive portraits.

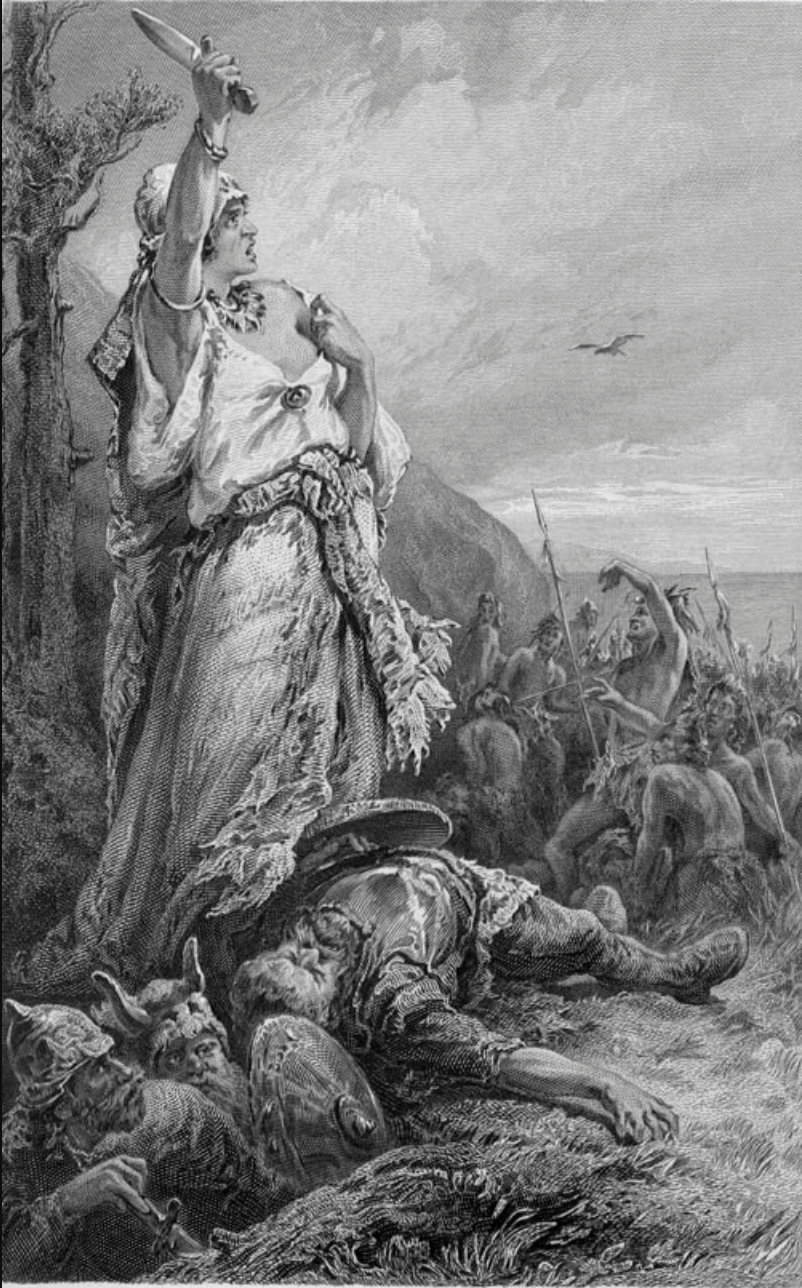

In Eirik the Red's Saga, Eirik's daughter, Freydís Eiríksdóttir, finds herself at the center of a battle with the indigenous peoples of Greenland and Canada while heavily pregnant. These warriors were equipped to defend themselves with weapons never seen by Norsemen, described in the saga as war-slings or catapults.

While the Norsemen retreated, Freydís cried out "Let me but have a weapon, I think I could fight better than any of you," which nobody really paid attention to. The men continued to flee, and the heavily pregnant Freydís struggled to keep up.

Surely vexed, she picked up the sword of a dead Norseman, turned on the attackers, "let down her sark [dress] and struck her breast with the naked sword." Apparently, this terrified the attackers into a swift retreat. Afterwards, the Norsemen seemed to give little fanfare to Freydís's raw courage.

"While we are careful not to present simplified narratives about pregnant warrior women, we must acknowledge that at least in art and stories, ideas were circulating about pregnant women with martial equipment," Eriksen says.

"Freydís's behaviour is surprising, but may find a parallel in the study's examined silver figurine, where a pregnant woman, arms embracing her protruding belly, is wearing what appears to be a helmet with a noseguard."

Another story, from The Saga of the People of Laxardal, tells how the pregnant Guðrún Ósvífrsdóttir is provoked by her husband's killer, Helgi Harðbeinsson. Wiping his bloodied spear on the shawl covering Guðrún's pregnant belly, Helgi says, "I think that under the corner of that shawl dwells my own death," a prophecy that is realized later in the story, when Guðrún's son avenges his father's death.

"The fetus is already inscribed not only into the kinship system of the elite early Icelanders, but into complex relationships of feuds, alliances, and revenge," the authors note.

These stories, of course, reflect the experiences of and attitudes towards pregnancy of women with high-ranking social status. The authors suspect attitudes would be very different depending on the pregnant person's position in a society that was extremely hierarchical and included slaves.

"Together with legal legislation such as pregnancy being seen as a 'defect' in an enslaved woman to be bought, or children born to subordinate peoples being the property of their owners, it is a stark reminder that pregnancy can also leave bodies open for volatility, risk, and exploitation," says Eriksen.

Politics, the authors write, do not only happen on battlefields or through state formation. They argue that exploring the often-overlooked experiences of pregnant women will help archaeologists better understand past civilizations.

This research was published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.