In a promising new study, scientists have adapted an experimental cancer treatment to control celiac disease.

The method successfully quietened the gut's autoimmune reaction in tests using mice, suggesting the treatment could one day become a first-of-its-kind therapy for humans with the condition.

For the millions of people with celiac disease, even a small brush with gluten can trigger intestinal nastiness. Immune cells mistake the protein for a threat and launch an attack, leading to diarrhea, pain, and other unpleasant symptoms.

A team led by scientists at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland demonstrated a new immunotherapy that seems to quell this overreaction – in mice at least.

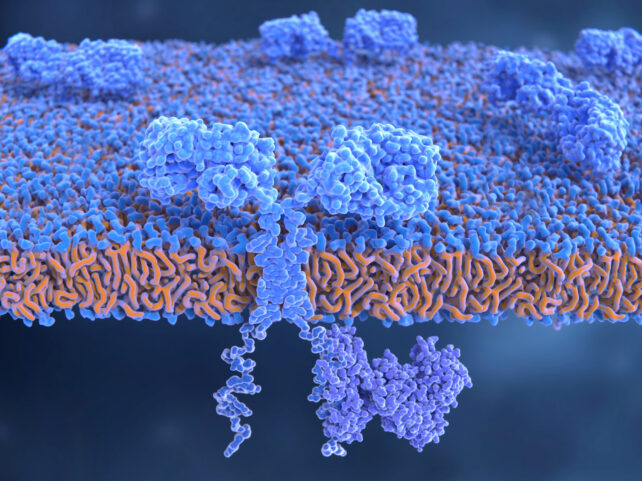

The researchers engineered regulatory T cells (T regs); a type of immune tissue that calms down the symptom-causing effector T cells. When untreated mice were fed gluten, the effector T cells gathered in the intestines and proliferated, ready for battle. But in mice that had been infused with the engineered T regs, the effector T cells didn't respond to the gluten, and didn't migrate to the gut.

The technique is similar to an emerging treatment for cancer called Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, where immune cells removed from the patient are engineered to better target specific cancer cells before being returned into the body to bolster the defence response.

Early results have shown promise against some forms of cancer, although it's not without its own risks. Ironically, using immunotherapy against celiac disease works almost the opposite way to cancer – suppressing immune responses rather than boosting them.

In the new study, the team engineered mice to have a particular genetic variation known as HLA-DQ2.5, which the majority of human celiac patients carry. They then developed effector T cells that reacted to gluten, as well as T regs that responded to those effector cells. Both types were then infused into the mice.

Interestingly, the mice that received the treatment not only seemed to be protected against the gluten antigen that their effector T cells were primed to attack, but the reaction was also suppressed for immune cells targeting a similar but distinct gluten antigen.

Hopes of a functional 'cure' should of course be tamped down for now – there's still a long road before human trials could begin.

"Although it looks promising, the study has several limitations," says Cristina Gomez-Casado, an immunologist at the University of Düsseldorf in Germany who was not involved in this research.

"1) it only studies the action of T regs against the wheat protein gliadin, so in the future it should be studied if they work against barley and rye proteins;

"2) it is not determined when T regs should be used as therapy (before developing the disease or once it has been diagnosed?);

"3) the mice used are not celiac, so gluten does not damage their gut, and are only offered once, so the long-term effect of gluten cannot be studied;

"4) it is known from other studies that the number of T regs is limited in celiac patients and, in some, they have been found to be non-functional."

Future work will need to address these issues, but still, the study lays some intriguing groundwork that could lead to new treatments for celiac disease. Patients could eventually be freed from carefully studying labels and menus, and being punished for days for slight slip-ups.

The research was published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.