The animal kingdoms of Asia and Australia are worlds apart, thanks to an invisible line that runs right between the two neighboring continents.

Most wildlife never cross this imaginary boundary, not even birds.

And so it has been for tens of millions of years, shaping animal evolution in different ways on each side.

It all started about 30 million years ago, when the Australian tectonic plate bashed up against the Eurasian tectonic plate and created an archipelago, rerouting ocean currents and creating new regional climates.

On one side of the map, in Indonesia and Malaysia, monkeys, apes, elephants, tigers, and rhinos evolved; while on the other side, in New Guinea and Australia, marsupials, monotremes, rodents, and cockatoos flourish. Very few species are abundant on both sides.

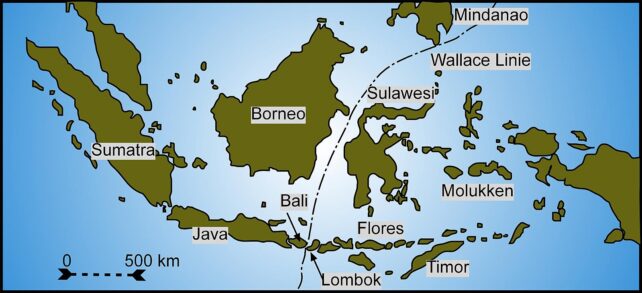

The curious faunal divide is named Wallace's Line – after the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who first noticed the stark difference in animal life (mostly mammals) while exploring the region in the mid-19th century.

"We may consider it established that the Strait of Lombok [between Bali and Lombok] only 15 miles wide [24 kilometers] marks the limit and abruptly separates two of the great zoological regions of the globe," Wallace wrote.

The naturalist later went on to independently develop a theory of evolution around the same time as Charles Darwin. The line he drew on a map more than a century ago is still considered a hypothetical evolutionary barrier, although debates continue as to its exact location and mechanisms.

Generally speaking, Wallace's line separates a shelf of the Asian continent from a shelf of the Australian tectonic plate. It is a geological line, but it is also a climatic and biological one.

Deep ocean channels like the Lombok Strait separate each shelf, which makes it difficult for animals to cross. Even when sea levels in the distant past were much lower than today, this chasm would have still existed.

While Wallace's invisible line is most obvious when comparing mammals in Asia and Australia, it also exists for birds, reptiles, and other animals.

Even creatures with wings don't typically make the trip across Wallace's line, and in the ocean, some types of fish and microbes show genetic differences on one side of the border compared to the other, indicating very little mixing between populations.

Scientists have yet to figure out what invisible barriers are holding these species back. Habitat and climate, however, are probably factors accentuating the evolutionary divide.

In 2023, an analysis of more than 20,000 vertebrate species found that Southeast Asian lineages evolved in a relatively tropical ancient environment that allowed them to spread out toward New Guinea on humid island "stepping stones".

Wildlife on the Australian continental shelf, meanwhile, evolved in distinctly drier conditions, which dictated a different evolutionary path. This meant that Australian wildlife was at a disadvantage in the tropical islands nearer the equator.

The more researchers study the Wallace line, however, the less clear it becomes about where the line should be drawn and how 'porous' the barrier might be – at least to some animals that can swim, float, or fly, like bats, beetles, monitor lizards, or macaques.

Wallace's divide isn't an absolute border, but more of a gradient, scientists say. Even still, the blurry line helps us make sense of animal evolution for thousands of species.

"Darwin's and Wallace's mental and actual maps were the table on which the evolutionary scheme was played out, comparable in importance to the geological time scale," argued science historian Jane Camerini in 1993 for the History of Science Society.

What started as a single, roughly placed line, drawn more than a century ago, has now helped shape a bigger and more complicated picture of the natural world and its mysteries.