A dozen volunteers with severe type 1 diabetes showed clear improvements in their condition 12 months after receiving a revolutionary stem cell treatment, with all but two dropping their insulin therapy altogether.

The phase 1/phase 2 clinical trial results provide hope for the 8.4 million people around the world with type 1 diabetes; an autoimmune condition where the immune system damages insulin-producing cells.

While more extensive studies are required to see how long the benefits of the treatment can last, the new therapy developed by Boston-based Vertex Pharmaceuticals provides strong evidence that it's possible to replace the body's lost insulin production using infusions of stem cells.

Related: A Distinct New Form of Diabetes Has Been Officially Recognized

People with type 1 diabetes are dependent on a precarious balance of insulin therapy for their whole lives. If their insulin drops too low, cells are unable to make use of the sugar in their bloodstream, leading to a buildup that can damage organs. If insulin is too high, patients are plunged into hypoglycemia, which can result in a loss of consciousness, seizures, coma, or death.

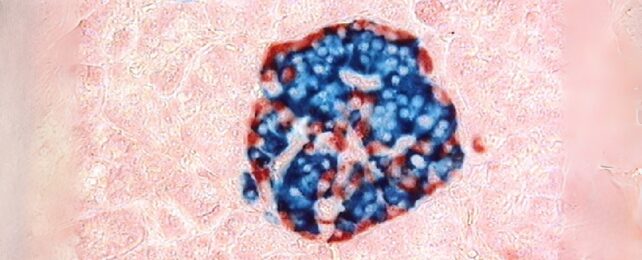

The pancreas's islet cells are responsible for maintaining most of our bodies' insulin levels. Donor transplants of healthy versions of these cells have shown promise in treating type 1 diabetes in the past, but multiple donors are required, and donors are rare.

So University of Toronto surgeon Trevor Reichman and colleagues infused 12 patients with islet cells derived from human stem cells in a treatment known as zimislecel.

The patients also received immunosuppressive treatment before and after their zimislecel infusion. The islets not only produced insulin inside their bodies, but they did so at safe levels, reducing the patients' dependence on costly doses of insulin.

"These findings showed that zimislecel islet cells were functional and self-regulated appropriately," the researchers write in their paper.

The mild to moderate side-effects, including decreased kidney function and the anticipated drop in immune cells, were all linked with the immunosuppressive therapy. Sadly, two additional participants died during the trial; one from an infection arising from surgery and the other from complications due to an unrelated condition.

As there were no serious adverse events attributed to the new islet cell therapy, the clinical trials are have progressed into phase 3.

"These findings provide evidence that pancreatic islets can be effectively produced from pluripotent stem cells and used to treat type 1 diabetes," Reichman and team conclude.

This research was published in NEJM.