The producer of the world's most popular weedkiller – Roundup – is replacing a notorious ingredient with what could be a "regrettable substitution".

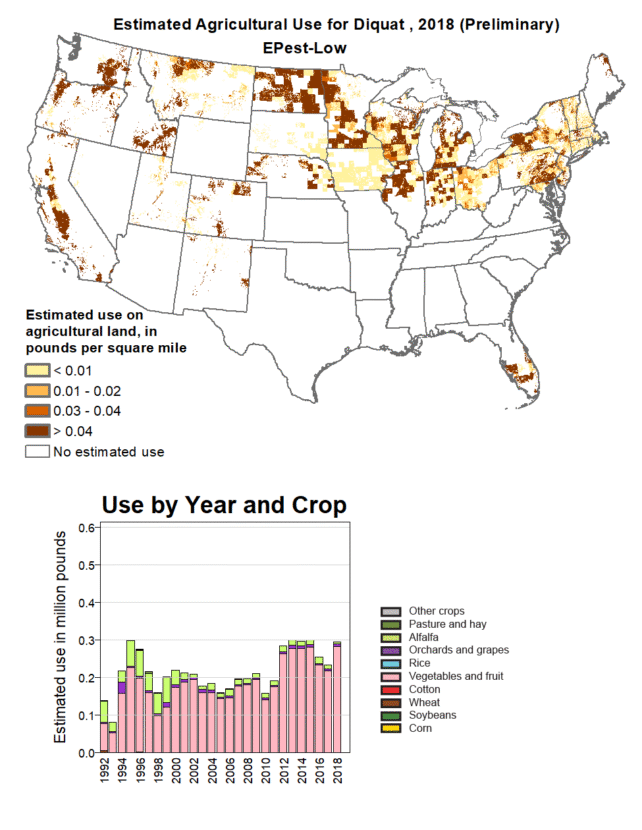

As scrutiny grows over the health risks of glyphosate, the herbicide diquat is increasingly used in its place.

A fresh analysis from researchers in China, however, suggests that the alternative is not without its harms. In fact, at some concentrations, it can cause irreversible damage to organs.

Diquat is a close cousin of paraquat – a herbicide that is 28 times more toxic than glyphosate and that is banned in 70 countries. Glyphosate was initially introduced as a safer alternative to paraquat; however, both chemicals now face scrutiny for their potential health effects.

Related: Controversial New Study Links Parkinson's With Living Near a Golf Course

Diquat has begun to rapidly take their place.

Like paraquat, diquat is well known to be toxic, which is why it must be handled with protective gear, but there is disagreement on precisely what levels of exposure are safe.

Even though diquat is less easily absorbed by the lungs, it can still damage the skin, and ingestion remains a serious risk.

The European Union banned diquat from 2018 because of the 'high risk' it poses to workers, bystanders, and residents.

Switzerland and the United Kingdom have also banned the chemical for its potentially harmful health effects. Neither paraquat nor diquat is banned in the US.

Analyzing the latest research, scientists in China, led by Cheng He of the Suining Central Hospital, have now identified all the ways in which diquat may disrupt our health.

"Although diquat exhibits lower acute toxicity compared to the related herbicide paraquat, it still poses a significant threat to ecosystems due to its potential for bioaccumulation and long-term persistence in soil and water bodies," argues the team.

The health effects are mostly understood through reports of acute poisonings and animal studies, but the signs don't look good.

When absorbed through the gut, diquat can spread throughout the body's tissues. The herbicide that is not excreted through faeces or urine usually goes on to cause acute kidney injury. Liver dysfunction is also common, and lung and nervous system injuries have also been reported.

In fact, at high enough concentrations, diquat poisoning can lead to multiple organ failure and even death.

Autopsy studies of those who have died from diquat poisoning suggest that not all the herbicide is absorbed by the gut. Some of the chemical sticks around in the digestive tract, possibly disrupting the microbiome and weakening the gut lining.

"The gut plays a crucial role in the poisoning process," argues the team from Suining Central Hospital.

"The intestine is not only the primary route of exposure but also a central target of [diquat's] toxic effects."

In Brazil, where diquat is popular and where protective gear is limited, local farmers have reported disturbing poisonings associated with the herbicide spray.

In the US, diquat-related illnesses have been recorded for years now.

While herbicides can help farms with their profits and boost crop yields, they also come with serious potential downsides to human and environmental health.

Replacing one toxic substance with another does little to solve the problem, it merely prolongs it.

The study was published in Frontiers in Pharmacology.