It's easy to assume nuclear war only affects those close enough to see that most terrifying of clouds. In reality, the devastation could stretch around the world.

A new study shows just how badly global food production would fare under different nuclear winter scenarios.

Nuclear winter is a devastating climate effect theorized to follow large-scale nuclear conflict where blasts of nuclear weapons and the resulting firestorms inject huge amounts of soot and dust into the atmosphere. This would reduce the amount of sunlight reaching the surface for years at a time, in turn killing off many plants and animals – including those we rely on for food.

Related: We've Forgotten The Potential Horrors of What a Nuclear Winter Would Be Like

A new study, led by scientists at Pennsylvania State University in the US, simulated the effects that nuclear winter would have on global food production. Being the widest-grown grain in the world, corn (Zea maize) was used as a 'sentinel' crop, allowing the team to estimate what would happen to agriculture as a whole.

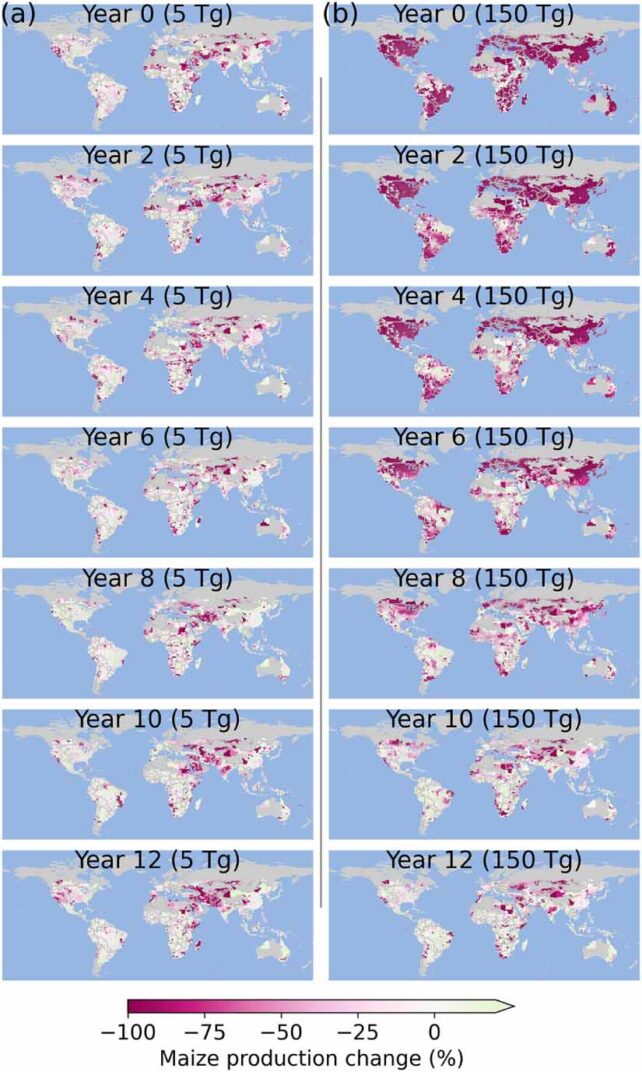

"We simulated corn production in 38,572 locations under the six nuclear war scenarios of increasing severity – with soot injections ranging from 5 million to 165 million tons," says Yuning Shi, plant scientist and meteorologist at Penn State.

Unsurprisingly, the outcomes weren't great. The team found that a localized nuclear war, which injected 'only' 5.5 million tons of soot into the atmosphere, would still reduce global corn production by 7 percent. However, a global-scale conflict that unleashed 165 million tons could cut crop production by 80 percent.

That worst-case scenario also has a damage multiplier added: dissolving the planet's protective ozone layer.

"The blast and fireball of atomic explosions produce nitrogen oxides in the stratosphere," says Shi. "The presence of both nitrogen oxides and heating from absorptive soot could rapidly destroy ozone, increasing UV-B radiation levels at the Earth's surface. This would damage plant tissue and further limit global food production."

The team estimates that UV-B would peak between six and eight years after a nuclear war, reducing corn production by an extra 7 percent. That's an alarming 87 percent total drop in crop production, which would amount to a global food crisis.

The simulations suggest that it could take between 7 and 12 years for global corn production to recover from nuclear winter, depending on the severity of the war. Generally, the Southern Hemisphere would recover faster than the Northern, and regions closer to the equator faster than those closer to the poles.

There are things humans could do to speed up recovery, though. Switching to varieties of corn that can grow better under cooler conditions and in shorter growing seasons could reduce the loss of crop productivity by up to 10 percent. That could help, but it would of course still be better to just not have a nuclear winter at all.

If we simply must, however – and the current state of global politics makes the scenario more likely than it has been since the Cold War – then the team proposes preparing "agricultural resilience kits." These would be made up of crop seeds chosen to be the best fit for each region for proposed climate possibilities.

"These kits would help sustain food production during the unstable years following a nuclear war, while supply chains and infrastructure recover," says Armen Kemanian, lead developer of the simulations. "The agricultural resilience kits concept can be expanded to other disasters – when catastrophes of these magnitude strike, resilience is of the essence."

And before you ask: no, nuclear winter would not cancel out global warming.

The study was published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.