There's a lot to be said for an optimistic outlook, but a new study suggests that interpreting other people's emotions as more positive than they actually are could be a sign of brain aging and mental decline.

This 'positivity bias' is known to happen as we get older. According to socioemotional selectivity theory, it's a mechanism that helps us focus on the good as our futures shrink, protecting mental well-being by downplaying the negative.

But a team of researchers from the UK and Israel suggests something different: that the bias is actually a sign of cognitive decline and could even be an early warning for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's.

Related: Feeling Happy And Sad? Here's How Our Brains Manage Mixed Emotions.

"Our study supports the idea that age-related positivity reflects neurodegeneration, but this requires confirmation in future longitudinal studies," write the authors in their published paper.

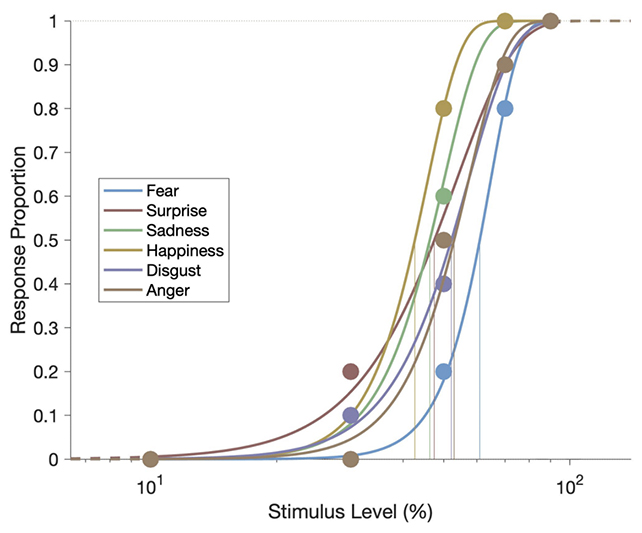

The study recruited 665 participants aged 18–89, split into roughly 10-year age groups. The volunteers were asked to identify emotions in computer-generated faces. They also underwent MRI brain scans and were tested for signs of cognitive decline and depression.

As expected, older people identified faces as showing positive emotions more readily than younger people, while they were less likely to label faces as negative. Ambiguous or hard-to-read faces were most often interpreted as positive by older participants.

Data from the brain scans linked this positivity bias with less gray matter in the brain's hippocampus and amygdala, areas tasked with processing emotions.

Being more likely to interpret facial emotions as positive was also associated with worse cognitive performance, but not with depressive symptoms. That important distinction backs up the idea that the bias emerges from deterioration in certain parts of the brain.

"The lack of association with depressive symptoms suggests that positivity bias could help distinguish cognitive decline from depression in old age," write the researchers.

It adds to previous research linking cognitive decline with an inability to recognize emotions – something that's also been seen in the early stages of Alzheimer's. The results suggest the part of the brain that reads emotion in others is somehow damaged by the onset of dementia.

The negative emotions presented in these experiments, which included anger, fear, and sadness, are known to be harder to spot than positive emotions such as happiness, which also goes some way to explaining these results.

The researchers note that this study represents a single point in time. It doesn't track the same people as they age, and as their cognitive abilities and emotion recognition skills change, so cause and effect remains uncertain. That's something future studies might be able to address.

When it comes to age-related cognitive decline and dementia, there are so many contributing factors that it can be difficult to get a clear picture. But this points to a potential new tool for detecting dementia earlier – when intervention and support can make the biggest difference.

"We are exploring how these findings relate to older adults with early cognitive decline, particularly those showing signs of apathy, which is often another early sign of dementia," says neuroscientist Noham Wolpe, from Tel Aviv University in Israel.

The research has been published in the Journal of Neuroscience.