Chocolate connoisseurs, rejoice: scientists have dug deep into cacao bean fermentation, a crucial part of the chocolate-making process, to come up with a list of key environmental factors that influence chocolate flavor.

It should now be easier to consistently make better-quality chocolate across the globe on a larger scale, in the same way that premium beers and cheeses are produced to specific recipes.

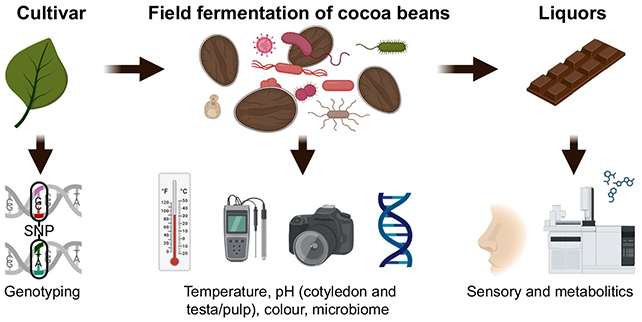

Led by a team from the University of Nottingham in the UK, the research involved a careful study of cacao bean (Theobroma cacao) farms in Colombia, where the acidity, temperature, and microbe conditions of the fermentation process were tracked.

Related: Largest Insect on Earth Headed For Extinction Thanks to Our Love of Chocolate

"This work lays the foundation for a new era in chocolate production, where defined starter cultures can standardize fermentation, unlock novel flavor possibilities, and elevate chocolate quality on a global scale," says molecular biologist David Gopaulchan, from the University of Nottingham.

The fermentation stage is key to the flavor of chocolate, and varies depending on location – which we now know is part of the reason why chocolate tastes different from different parts of the world. Through their analysis, the researchers picked out the microbial and chemical conditions for chocolate with a finer taste.

They then developed a simplified microbe community, made up of five bacteria and four fungi, that could produce the same fermentation conditions in the lab. The idea is that this could be used as a 'starter kit' for farms to standardize fine chocolate production and give more of a tickle to our tastebuds.

At the moment, the fermentation process is largely uncontrolled and spontaneous: it's left to happen naturally, in other words. Some farms produce finer-tasting chocolate, while others are left with 'bulk' chocolate that has a more bitter taste – something that had previously been put down to genetics.

"Fermentation is a natural, microbe-driven process that typically takes place directly on cocoa farms, where harvested beans are piled in boxes, heaps, or baskets," says Gopaulchan.

"In these settings, naturally occurring bacteria and fungi from the surrounding environment break down the beans, producing key chemical compounds that underpin chocolate's final taste and aroma."

In the future, we might see chocolate brands developing their own distinct flavors, which are consistent across multiple products. However, this is very much a 'proof of concept' at the moment – it's not immediately clear how this might be used commercially, which will take some working out.

What we can say is that this research has the potential to increase the amount of fine flavor cocoa available on the market (right now around 12 percent of produced chocolate is regarded as fine flavor), as well as reducing the waste produced by bad fermentations

Through a better understanding of fermentation and how it influences the taste potential of the processed cocoa bean, we might see a more made-to-order chocolate industry – but bear in mind that the tasty treat comes with a number of unhealthy ingredients, too, as well as some unexpected health benefits.

"This research signals a shift from spontaneous, uncontrolled fermentations to a standardized, science-driven process," says Gopaulchan.

The research has been published in Nature Microbiology.