An immunocompromised man endured ongoing acute COVID-19 for more than 750 days. During this time, he experienced persistent respiratory symptoms and was hospitalized five times.

In spite of its duration, the man's condition differs from long COVID as it wasn't a case of symptoms lingering once the virus had cleared out, but the viral phase of SARS-CoV-2 that continued for over two years.

While this record may be easy to dismiss as something that occurs only to vulnerable people, persistent infections have implications for us all, US researchers warn in their new study.

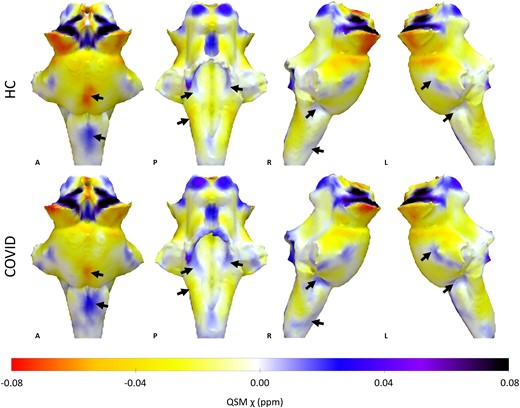

Related: COVID's Hidden Toll: Full-Body Scans Reveal Long-Term Immune Effects

"Long-term infections allow the virus to explore ways to infect cells more efficiently, and [this study] adds to the evidence that more transmissible variants have emerged from such infections," Harvard University epidemiologist William Hanage told Sophia Abene at Contagion Live.

"Effectively treating such cases is hence a priority for both the health of the individual and the community."

Boston University bioinformatician Joseline Velasquez-Reyes and colleagues' genetic analysis of viral samples collected from the patient between March 2021 and July 2022 revealed what the virus was up to during its extended invasion.

The virus's mutation rate within the patient ended up similar to that usually seen across a community. What's more, some of these mutations were awfully familiar. Spike mutations matched positions of those seen in the omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, for example.

Within just one person, the same types of mutations that led to the emergence of the faster multiplying omicron variant were on their way to being repeated. This backs the theory that omicron-like changes developed from selection pressures the virus experiences inside our bodies, the researchers explain.

The patient, who has advanced HIV-1, believes they contracted SARS-CoV-2 in mid-May of 2020. During this time, he was not receiving antiretroviral therapy, nor able to access the necessary medical care despite suffering from respiratory symptoms, headaches, body aches, and weakness.

The 41-year-old had an immune helper T-cell count of just 35 cells per microliter of blood, explaining how the virus managed to persist for so long. The healthy range is 500 to 1,500 cells per microliter.

Luckily, in this case at least, the stubborn invader was not highly infectious.

"The inferred absence of onward infections might indicate a loss of transmissibility during adaptation to a single host," Velasquez-Reyes and team suspect.

Still, there's no guarantee other infections that establish long-term camps inside us will follow the same evolutionary path, which is why experts are wary and calling for continued close monitoring of COVID and adequate access to healthcare for everyone.

"Clearing these infections should be a priority for health-care systems," the researchers conclude.

To reduce the chances of problematic mutations, physicians and researchers urge communities to keep up vaccinations and continue masking in crowded, enclosed areas.

This research was published in The Lancet.