Ancient Egyptian guards may have used a tiny cow bone with a hole drilled into it to keep royal tomb workers in order.

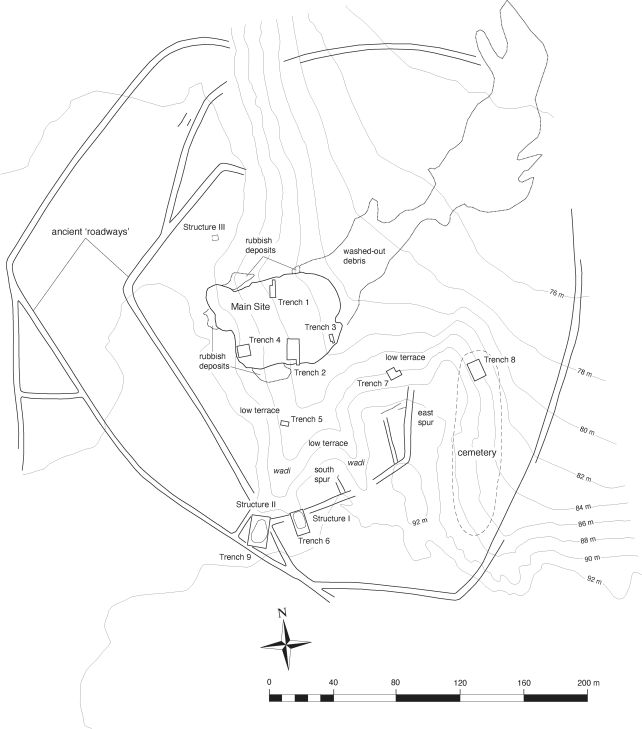

The strange artifact was discovered in the Akhetaten Stone Village, a workers' settlement located near the royal cemetery, dating back to the Eighteenth Dynasty, approximately 3,300 years ago.

An in-depth analysis has now revealed that not only would the bone have functioned as a whistle, but also that there are very few other things it could be.

Related: Oldest Egyptian DNA Reveals Secrets of Elite Potter From Pyramid Era

According to a team led by archaeologist Michelle Langley of Griffith University in Australia, the most likely use of the whistle would have been either to communicate across the settlement or possibly to manage the working dogs that accompanied guards on their patrols.

"Found at the Stone Village, a peripheral workers' settlement, this object fits with ideas that this community was heavily policed because of their proximity to the royal cemetery and likely connection to work on the royal tombs," the researchers write in their paper.

"Significantly, this object is the first of its kind identified in a dynastic context and demonstrates the potential insights that wait to be gained from intensive examination of Egypt's osseous technologies."

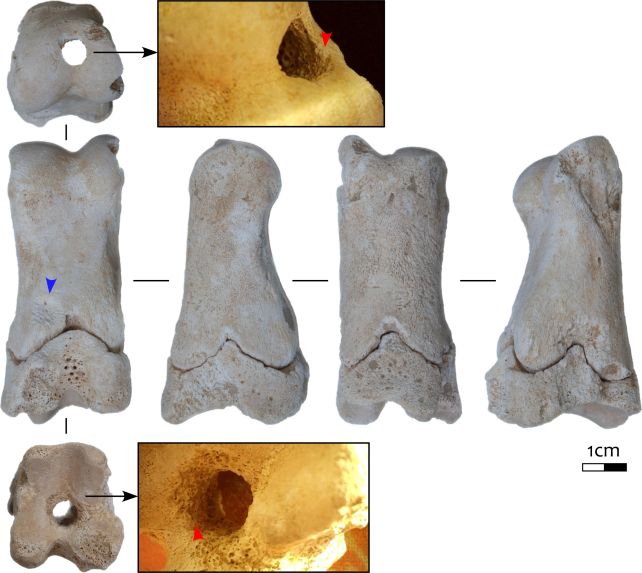

The bone itself is unassuming: the first phalanx of a juvenile bovine, measuring just 6.3 centimeters (2.5 inches) in length. It's both uncooked and unworked, with the exception of a single hole drilled right through the length of the bone.

Figuring out the purpose of the artifact involved multiple steps, beginning with a close examination of the hole. Finding it to be clean and straight strongly suggested it had been deliberately made.

Careful microscopy confirmed it: the researchers found striations from the drilling process around the hole's edges. Other marks on the bone were linked to termite damage.

Next, a visual examination of the bone helped narrow down what it isn't. Possible uses included toys, decorative figurines, amulets, containers, handles, or hunting whistles.

The researchers systematically considered these options and conclusively ruled out all but the last. The ancient Egyptians are well known for their decorative work, and other examples of these objects in the archaeological record are much more heavily adorned than a simple bone with a single hole.

Nor would the bone have functioned as a container. It's the wrong shape and too small to be of much use for containing things. Similarly, a bone handle would typically show signs of wear from use, and these signs were not present in the artifact.

Noting that the bone resembles whistles found in other cultures, the researchers crafted a version of their own with a fresh cow toe bone, using the Akhetaten bone as a blueprint.

"In testing … A high-pitch tone was produced, and with practice, this tone could achieve significant volume," they write in their paper.

This shrill tone, they felt, dramatically reduced the already small likelihood that the whistle was used for hunting. As it was, nothing in the surrounding archaeology suggested hunting had been practiced by the local inhabitants. What's more, hunting whistles typically mimic the calls of prey birds – something this instrument didn't at all sound like.

On the other hand, artifacts in the area suggest a military presence, and access to the nearby royal tombs would have been heavily restricted and policed. Although we can't know for sure, it seems feasible that the whistle may have been used much like security personnel use whistles in the present day, thousands of years later.

"This research also highlights the value of considering what appear to be the most mundane of items among a wealth of bright and glittering material culture," the researchers write.

"Not all that was made and used by Dynastic Egyptians was made from heated, transformed, and molded materials, and even the most basic, uncooked bone could represent a significant insight into the Egyptian past."

The research has been published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.