A new study finds autism and schizophrenia may lie at the crux of what makes humans uniquely intelligent.

"Our results suggest that some of the same genetic changes that make the human brain unique also made humans more neurodiverse," says Stanford University neuroscientist Alexander Starr.

While both autism and schizophrenia are neurodevelopmental brain differences that can have a mix of negative and positive impacts (including increased creativity), to be very clear, the new study's findings don't indicate that neurodivergent people are more or less intelligent; that's not at all what was measured here.

Rather, the researchers found that genes responsible for human intellect also increase our chances of having autistic or schizophrenic traits.

Related: Autism Can Boost Cognitive Performance, And We May Finally Know Why

As it is rare to find the behavioral traits of autism or schizophrenia in non-human primates, Starr and colleagues suspected there may be a genetic reason these conditions seem to be unique to humans.

So they compared RNA from over a million cells across three brain regions in six mammalian species: mice, marmosets, rhesus macaques, gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans.

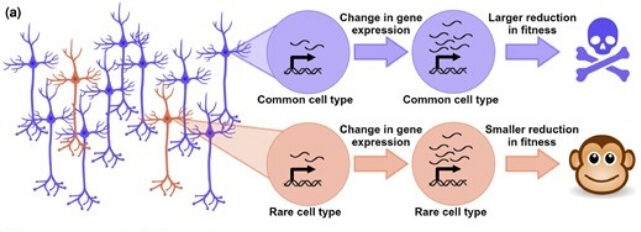

The team found that generally, the most common types of brain cells stayed relatively unchanged, even between species. There was one major exception, however: the most abundant type of neocortical neurons, layer 2/3 intratelencephalic excitatory neurons, changed much quicker in humans than other primates across evolutionary time.

The same pattern was confirmed across multiple databases, and using brain organoids made from chimp and human cells.

The neocortical part of the brain is involved with high-order functioning, including cognition, reasoning, and language. The rapid transformation of specialized neurons in this region includes changes in genes associated with autism and schizophrenia.

It's still unclear why these genes helped our human ancestors survive, but as some of the genes have been associated with a delay in brain development, the researchers suspect these changes may have helped increase our capacity for language and complex thinking. These traits have clear advantages, even if they also increase the chances of certain neurodevelopmental conditions.

Perhaps the best-known example of this type of evolutionary trade-off is in human populations living in regions with malaria. People here have a higher chance of developing sickle cell anemia because the gene behind the condition also conveys a 30 percent reduction in susceptibility to the malaria parasite.

"Our findings provide the strongest evidence to date supporting the long-standing hypothesis that natural selection for human-specific traits has increased the likelihood of certain disorders," Starr and team explain in their paper.

"The exceptionally high prevalence of autism in humans may be a direct result of natural selection for lower expression of a suite of genes that conferred a fitness benefit to our ancestors while also rendering an abundant class of neurons more sensitive to perturbation."

They caution, however, that while they have established a correlation, more research is required to understand the drivers of the strong selection forces they've uncovered. If their suspicions are correct, it would mean humans wouldn't exist as we are without the existence of autism.

Currently, a little over 3 in 100 children in the US are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. This is controversially increasing (only slightly, to about 4 in 100), due to increased awareness of autistic traits and the broadening of diagnostic criteria.

The new study adds to a mountain of evidence that autism is genetic, with up to 80 percent of cases linked to inherited gene mutations. New mutations likely account for the remaining 20 percent. A similarly high level of heritability is seen in schizophrenia as well.

This research was published in Molecular Biology and Evolution.