Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, and happens when the cartilage protecting joints gets worn down. It's painful and debilitating, but new research suggests that low-dose radiation therapy (LDRT) may work as a countermeasure.

Researchers from across South Korea ran a clinical trial involving 114 people with knee osteoarthritis to compare two different doses of LDRT and a sham treatment, which had no actual radiation. Participants were not aware of which group they were in.

Those given the higher dose of LDRT, administered over six sessions, reported significantly greater improvements in pain, physical function, and their overall condition, compared to the other two groups (though there was some evidence of a placebo effect as well).

Related: Can Vitamin D Slow Aging? A New Study Says Yes – But There's a Catch

This won't restore cartilage in severe osteoarthritis, where that tissue is already gone, but LDRT shows promise as a way of managing symptoms and making osteoarthritis more tolerable. Further tests are planned to see if there's any change in joint structure as well.

"People with painful knee osteoarthritis often face a difficult choice between the risks of side effects from pain medications and the risks of joint replacement surgery," says radiation oncologist Byoung Hyuck Kim, from the Seoul National University College of Medicine.

"There's a clinical need for moderate interventions between weak pain medications and aggressive surgery, and we think radiation may be a suitable option for those patients especially when drugs and injections are poorly tolerated."

As the researchers point out, there are already some ways to tackle osteoarthritis and its consequences, including losing weight (to reduce pressure on the joints) and standard pain relief medication.

In fact, LDRT is already used quite extensively as a treatment option as well – but not in the US. There remains conflicting data on how effective these radiation doses can be, which is partly why this new trial was done.

A sham treatment group was included to help isolate the effects of the LDRT, and there were also limits put on the amount of pain relief medication that volunteers could take (which has been an issue in earlier studies).

Part of the reason there's still some uncertainty around LDRT for osteoarthritis is down to the harms that radiation can cause, if not properly managed. The doses given here were less than 5 percent of those typically given for cancer treatments, and according to the researchers, no radiation-related side effects were reported by the study participants.

"There is a misconception that medicinal, or therapeutic, radiation is always delivered in high doses," says Kim. "But for osteoarthritis, the doses are only a small fraction of what we use for cancer, and the treatment targets joints that are positioned away from vital organs, which lowers the likelihood of side effects."

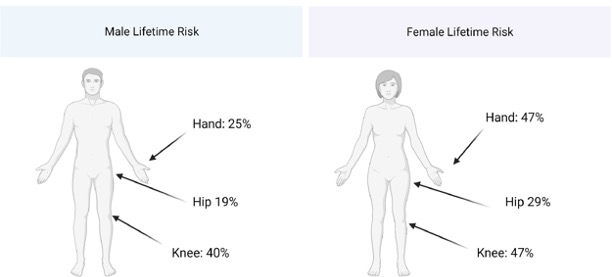

Osteoarthritis is thought to affect around 595 million people globally, and has a real impact on physical capabilities and quality of life. It most frequently starts after the age of 40, and the risk steadily increases with age.

"For severe osteoarthritis, where the joint is physically destroyed and cartilage is already gone, radiation will not regenerate tissue," says Kim. "But for people with mild to moderate disease, this approach could delay the need for joint replacement."

The research was presented at the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) Annual Meeting.