Rising seas threaten millions of lives and livelihoods in coastal regions, along with untold swaths of vital infrastructure. A new study clarifies, for the first time, the overall danger rising sea levels pose to built environments in the Global South.

"Everyone of us will be affected by climate change and sea level rise, whether we live by the ocean or not," says Eric Galbraith, an earth scientist at McGill University in Canada who co-authored the new study.

"We all rely on goods, foods, and fuels that pass through ports and coastal infrastructure exposed to sea-level rise. Disruption of this essential infrastructure could play havoc with our globally interconnected economy and food system."

Earth's atmosphere holds more carbon dioxide today than it has in at least 4 million years, well before the dawn of modern humans. This is causing unprecedented problems for life on Earth, from disastrous weather to the insidious creep of seawater into civilization.

Related: Alarming Sea Level Rise Expected Even With 1.5°C Warming Limit

Sea levels have risen before in human history, including a sharp rise 10,000 years ago, as we emerged from the last ice age. But coastal communities were much smaller, simpler, and sparser back then, a far cry from the bustling conurbations now widely entrenched in harm's way.

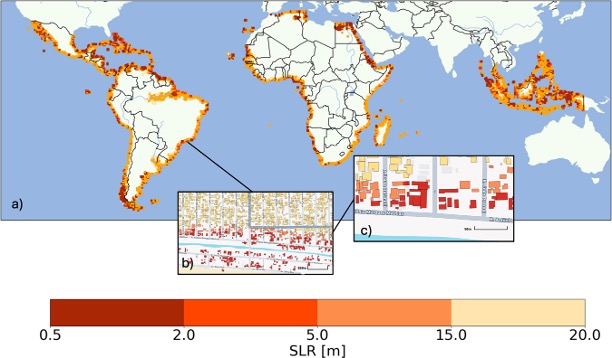

This new study is the first large-scale assessment mapping individual buildings and their vulnerability to sea-level rise, the authors note. It covers coastlines in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, and capitalizes on recent innovations in remote sensing and machine learning as well as new high-resolution topography and building-footprint data.

About a tenth of humanity, or close to 750 million people, live within 5 kilometers of the shoreline, which means even a modest increase in sea levels can spell deep trouble for lots of people.

"Sea-level rise is a slow but unstoppable consequence of warming that is already impacting coastal populations and will continue for centuries," says geophysicist and study author Natalya Gomez of McGill University.

"People often talk about sea level rising by tens of centimetres, or maybe a metre, but in fact it could continue to rise for many meters if we don't quickly stop burning fossil fuels."

The new study covered 840 million buildings across the Global South, used satellite data and detailed elevation maps, and considered three scenarios for local sea-level rise: 0.5 meters, 5 meters, and 20 meters.

Even with relatively ambitious cuts in CO2 emissions, sea levels are widely expected to rise by at least half a meter before 2100. In this more optimistic scenario of a 0.5-meter rise, researchers found roughly 3 million buildings would be inundated by coastal flooding.

That total grows to about 45 million buildings if the ocean rises by 5 meters, wiping out more than 80 percent of building stock in some countries, the researchers found. More than 130 million buildings would likely be inundated in the more dire scenario of 20 meters of sea-level rise.

Erosion, storm surges, and tidal intensification were not considered in the study, "making these results a minimum," the team writes in their paper.

"We were surprised at the large number of buildings at risk from relatively modest long-term sea-level rise," adds Jeff Cardille, an ecologist at McGill University and one of the study co-authors.

"Some coastal countries are much more exposed than others, due to details of the coastal topography and locations of buildings."

Since vulnerable buildings tend to be clustered in low-lying areas with dense populations, entire neighborhoods are often at risk, in addition to important ports and other industrial districts.

Studies like this are useful not only for evaluating risks to existing infrastructure, but they can also help urban planners minimize risks to developments still in the works.

The researchers produced an interactive map identifying areas of greatest risk, which could help inform new land-use strategies and adaptive designs, or guide difficult decisions about whether and when communities should relocate away from the coast.

While local rates vary, global sea levels are now rising by about 4.5 millimeters per year, a pace that's expected to continue increasing for decades.

"There is no escaping at least a moderate amount of sea-level rise," says Maya Willard-Stepan, an environmental scientist now at the University of Victoria in Canada.

"The sooner coastal communities can start planning for it, the better chance they have of continuing to flourish."

The study was published in npj Urban Sustainability.