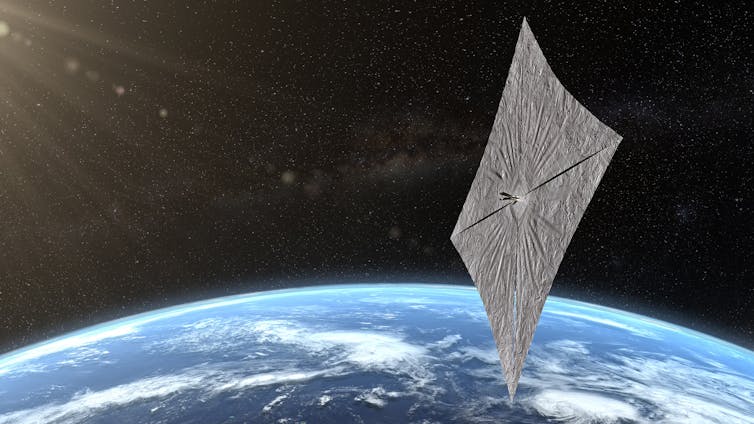

A proposed constellation of satellites has astronomers very worried. Unlike satellites that reflect sunlight and produce light pollution as an unfortunate byproduct, the ones by US startup Reflect Orbital would produce light pollution by design.

The company promises to produce "sunlight on demand" with mirrors that beam sunlight down to Earth so solar farms can operate after sunset.

It plans to start with an 18-metre test satellite named Earendil-1 which the company has applied to launch in 2026. It would eventually be followed by about 4,000 satellites in orbit by 2030, according to the latest reports.

Related: Sunlight Can Still Damage Skin Through a Closed Window. Here's How.

So how bad would the light pollution be? And perhaps more importantly, can Reflect Orbital's satellites even work as advertised?

Bouncing sunlight

In the same way you can bounce sunlight off a watch face to produce a spot of light, Reflect Orbital's satellites would use mirrors to beam light onto a patch of Earth.

But the scale involved is vastly different. Reflect Orbital's satellites would orbit about 625km above the ground, and would eventually have mirrors 54 metres across.

When you bounce light off your watch onto a nearby wall, the spot of light can be very bright. But if you bounce it onto a distant wall, the spot becomes larger – and dimmer.

This is because the Sun is not a point of light, but spans half a degree in angle in the sky. This means that at large distances, a beam of sunlight reflected off a flat mirror spreads out with an angle of half a degree.

What does that mean in practice? Let's take a satellite reflecting sunlight over a distance of roughly 800km – because a 625km-high satellite won't always be directly overhead, but beaming the sunlight at an angle. The illuminated patch of ground would be at least 7km across.

Even a curved mirror or a lens can't focus the sunlight into a tighter spot due to the distance and the half-degree angle of the Sun in the sky.

Would this reflected sunlight be bright or dim? Well, for a single 54 metre satellite it will be 15,000 times fainter than the midday Sun, but this is still far brighter than the full Moon.

The balloon test

Last year, Reflect Orbital's founder Ben Nowack posted a short video which summarised a test with the "last thing to build before moving into space". It was a reflector carried on a hot air balloon.

In the test, a flat, square mirror roughly 2.5 metres across directs a beam of light down to solar panels and sensors. In one instance the team measures 516 watts of light per square metre while the balloon is at a distance of 242 metres.

For comparison, the midday Sun produces roughly 1,000 watts per square metre. So 516 watts per square metre is about half of that, which is enough to be useful.

However, let's scale the balloon test to space. As we noted earlier, if the satellites were 800km from the area of interest, the reflector would need to be 6.5km by 6.5km – 42 square kilometres. It's not practical to build such a giant reflector, so the balloon test has some limitations.

So what is Reflect Orbital planning to do?

Reflect Orbital's plan is "simple satellites in the right constellation shining on existing solar farms". And their goal is only 200 watts per square metre – 20% of the midday Sun.

Can smaller satellites deliver? If a single 54 metre satellite is 15,000 times fainter than the midday Sun, you would need 3,000 of them to achieve 20% of the midday Sun. That's a lot of satellites to illuminate one region.

Another issue: satellites at a 625km altitude move at 7.5 kilometres per second. So a satellite will be within 1,000km of a given location for no more than 3.5 minutes.

This means 3,000 satellites would give you a few minutes of illumination. To provide even an hour, you'd need thousands more.

Reflect Orbital isn't lacking ambition. In one interview, Nowack suggested 250,000 satellites in 600km high orbits. That's more than all the currently catalogued satellites and large pieces of space junk put together.

And yet, that vast constellation would deliver only 20% of the midday Sun to no more than 80 locations at once, based on our calculations above. In practice, even fewer locations would be illuminated due to cloudy weather.

Additionally, given their altitude, the satellites could only deliver illumination to most locations near dusk and dawn, when the mirrors in low Earth orbit would be bathed in sunlight.

Aware of this, Reflect Orbital plans for their constellation to encircle Earth above the day-night line in sun-synchronous orbits to keep them continuously in sunlight.

Bright lights

So, are mirrored satellites a practical means to produce affordable solar power at night? Probably not. Could they produce devastating light pollution? Absolutely.

In the early evening it doesn't take long to spot satellites and space junk – and they're not deliberately designed to be bright. With Reflect Orbital's plan, even if just the test satellite works as planned, it will sometimes appear far brighter than the full Moon.

A constellation of such mirrors would be devastating to astronomy and dangerous to astronomers. To anyone looking through a telescope the surface of each mirror could be almost as bright as the surface of the Sun, risking permanent eye damage.

The light pollution will hinder everyone's ability to see the cosmos and light pollution is known to impact the daily rhythms of animals as well.

Related: ESA Report Says There's Too Much Junk in Earth Orbit Trunk

Although Reflect Orbital aims to illuminate specific locations, the satellites' beams would also sweep across Earth when moving from one location to the next. The night sky could be lit up with flashes of light brighter than the Moon.

The company did not reply to The Conversation about these concerns within deadline. However, it told Bloomberg this week it plans to redirect sunlight in ways that are "brief, predictable and targeted", avoiding observatories and sharing the locations of the satellites so scientists can plan their work.

The consequences would be dire

It remains to be seen whether Reflect Orbital's project will get off the ground. The company may launch a test satellite, but it's a long way from that to getting 250,000 enormous mirrors constantly circling Earth to keep some solar farms ticking over for a few extra hours a day.

Still, it's a project to watch. The consequences of success for astronomers – and anyone else who likes the night sky dark – would be dire. ![]()

Michael J. I. Brown, Associate Professor in Astronomy, Monash University and Matthew Kenworthy, Associate Professor in Astronomy, Leiden University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.