Usually, the chemical mist released when onions are chopped – propanethial S-oxide – makes our eyes water. Now scientists have found a simple way to keep those tears to a minimum.

In experiments by researchers from Cornell University in the US, sharper blades and slower cuts significantly reduced the amount of onion mist given off during preparation, keeping eyes drier and kitchen surfaces safer.

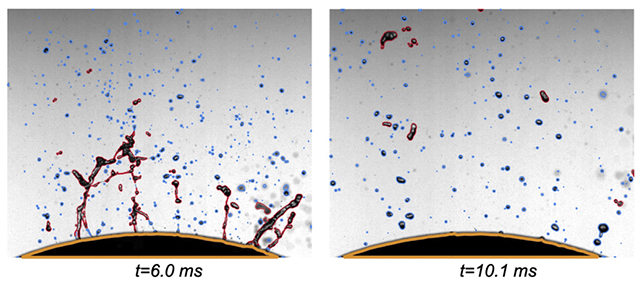

Biomechanist Zixuan Wu and team used a mini guillotine, a high-resolution camera, and sensors to carefully track the droplets expelled as onions were cut, comparing mist characteristics against knife sharpness, chopping speed, and cutting force.

Related: Scientists Reveal The Absolute Worst Thickness For a Paper Cut

"We found out the speed of the mist coming out is much higher compared to the speed of the blade cutting through," says physicist Sunghwan Jung.

Every layer in an onion has a top and bottom skin, and as those layers are breached, the analysis showed there are two resulting effects: an instantaneous explosion of mist, and then a slower seep of fluids through the layers.

Blunter knives created substantially more droplets and faster sprays, the researchers found. Because they require more force to break the skins, pressure builds in the onion's juices. Quicker, forceful cuts with a dull blade propelled droplets even farther.

The initial ejection of the droplets can be at very high speeds, the observations showed, and can get up to 40 meters per second – that's 144 kilometers (89 miles) per hour. It's these droplets that pose the greatest threats to eyes.

The researchers were also able to debunk the common theory that chilled onions give off less mist and are better at reducing tears related to chopping. The starting temperature of the onions didn't appear to make any real difference; if anything, chilling them made things worse.

"These observations were supported by theoretical models that accurately capture independently measured fracture forces," write the researchers in their published paper.

The history of onions in the kitchen stretches back some 5,000 years, and there's even a mention of the tears that live in an onion in Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra.

Now we have a much better idea of how the aerosols that cause those tears are created and released, and what can be done about it. Using sharp blades and gentle cuts keeps the droplet mist below eye level, the team found.

This discovery has implications for food safety, too. If bacteria are present, cutting style influences how they spread. As we saw with the E. coli outbreak at McDonald's in the US just last year, many people can get sick very quickly through pathogens spread by onions.

"Suppose you have pathogens on the very top layer on the onion," says Jung. "By cutting this onion these pathogens can become encapsulated in droplets where they can then spread."

The research has been published in PNAS.