If you've ever wondered why the giraffe has such a long neck, the answer seems clear: it lets them reach succulent leaves atop tall acacia trees in Africa.

Only giraffes have direct access to those leaves, while smaller mammals must compete with one another near the ground. This exclusive food source appears to allow the giraffe to breed throughout the year and to survive droughts better than shorter species.

But the long neck comes at a high cost. The giraffe's heart must produce enough pressure to pump its blood a couple of meters up to its head. The blood pressure of an adult giraffe is typically over 200mm Hg – more than twice that of most mammals.

Related: New Discovery Challenges Everything We Thought We Knew About Giraffe Necks

As a result, the heart of a resting giraffe uses more energy than the entire body of a resting human, and indeed more energy than the heart of any other mammal of comparable size.

However, as we show in a new study published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, the giraffe's heart has some unrecognized helpers in its battle against gravity: the animal's long, long legs.

Meet the 'elaffe'

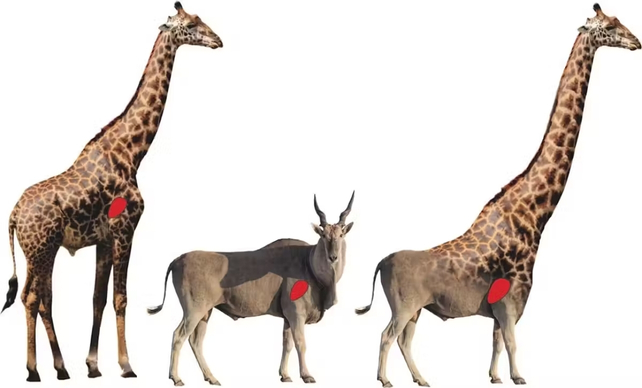

In our new study, we quantified the energy cost of pumping blood for a typical adult giraffe and compared it to what it would be in an imaginary animal with short legs but a longer neck to reach the same treetop height.

This beast was a Frankenstein-style combination of the body of a common African eland and the neck of a giraffe. We called it an "elaffe".

We found the animal would spend a whopping 21 percent of its total energy budget on powering its heart, compared with 16 percent in the giraffe and 6.7 percent in humans.

By raising its heart closer to its head by means of long legs, the giraffe "saves" a net 5 percent of the energy it takes in from food. Over the course of a year, this energy saving would add up to more than 1.5 tonnes of food – which could make the difference between life and death on the African savannah.

How giraffes work

In his book How Giraffes Work, zoologist Graham Mitchell reveals that the ancestors of giraffes had long legs before they evolved long necks.

This makes sense from an energy point of view. Long legs make the heart's job easier, while long necks make it work harder.

However, the evolution of long legs came with a price of its own. Giraffes are forced to splay their forelegs while drinking, which makes them slow and awkward to rise and escape if a predator should appear.

Statistics show giraffes are the most likely of all prey mammals to leave a water hole without getting a drink.

How long can a neck be?

The energy cost of the heart increases in direct proportion to the height of the neck, so there must be a limit. A sauropod dinosaur, the Giraffatitan, towers 13 meters above the floor of the Berlin Natural History Museum.

Its neck is 8.5m high, which would require a blood pressure of about 770mm Hg if it were to get blood to its head – almost eight times what we see in the average mammal. This is implausible because the heart's energy cost to pump that blood would have exceeded the energy cost of the entire rest of the body.

Sauropod dinosaurs could not lift their heads that high without passing out. In fact, it is unlikely that any land animal in history could exceed the height of an adult male giraffe.![]()

Roger S. Seymour, Professor Emeritus of Physiology, University of Adelaide and Edward Snelling, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.