The microbes in your mouth could have a profound impact on your blood sugar levels – and, in turn, your risk of diabetes or heart disease.

In a new study by researchers at King's College London and the University of Helsinki, 65 patients showed "exceptional improvements" in markers of blood sugar control after undergoing treatment for root canal infections.

These individuals did not receive a glucose tolerance test, but blood samples showed that within three months of treatment, surgical or non-surgical, signs of systemic inflammation in their blood had improved.

Two years on, several markers of metabolic health showed benefits as well.

The research team measured the cohort's serum glucose levels before the oral infections were treated. Two years after treatment, the group's glucose levels had significantly decreased, alongside markers of inflammation.

Related: Study Links Gum Disease With White Matter Damage in The Brain

A high blood sugar level is a leading risk factor for heart attacks and strokes.

"Our findings show that root canal treatment doesn't just improve oral health – it may also help reduce the risk of serious health conditions like diabetes and heart disease," says lead author and endodontologist Sadia Niazi from King's College London.

"It's a powerful reminder that oral health is deeply connected to overall health."

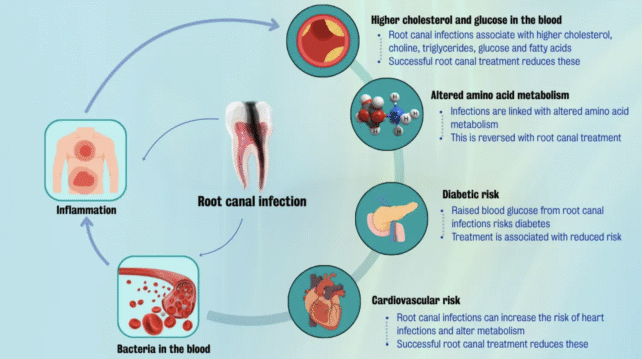

The study had no control group and was observational, meaning the results can't be used to determine cause and effect, but the team suspects that chronic infections of the tissues in and around the teeth may seep into circulation and trigger broader inflammatory changes, affecting the very chemistry of our blood.

This state of inflammation, in turn, could potentially influence insulin resistance and compromise blood sugar control.

That idea needs further testing, but the general premise is supported by emerging evidence linking oral health to death and disease.

Increasingly, evidence suggests that poor oral hygiene can take a toll on the cardiovascular system. In a recent, surprising study, published in September, scientists found oral bacteria in the arterial plaque of those with coronary artery disease.

According to some estimates, people with infectious lesions in and around their teeth may face more than double the risk of developing coronary artery disease down the road.

To test whether inflammatory markers, driven by oral infections, are linked to metabolic health, researchers turned to patients with apical periodontitis (AP) – a chronic inflammatory condition triggered by bacterial invasion into the pulp and root of teeth.

Blood samples were taken at five points: before root canal treatment, and then 3 months, 6 months, one year, and 2 years after treatment.

Researchers measured a total of 44 metabolites in the blood, either linked to inflammation or metabolism. Following root canal treatment, just over half of the metabolites had changed significantly, particularly amino acids, glucose, and lipids.

Three months after treatment, cholesterol had temporarily dropped. A key amino acid group associated with insulin resistance had also declined.

Improvements to blood glucose levels took longer to show up, appearing at the two-year mark. This coincided with a drop in pyruvate, a compound that affects inflammatory pathways.

If root canal treatment really can resolve cases of hyperglycemia, researchers think it could potentially mediate an individual's risk of developing serious cardiovascular consequences down the road.

One challenge with measuring metabolites in the blood, however, is that scientists still don't really know how they all function or interact. There are thousands of metabolites circulating that can be measured, yet we often only know which health conditions they are associated with.

Looking at just 44 metabolites can only give scientists a snapshot of what is going on, but the results are intriguing enough that the authors are calling for more research.

"It is vital that dental professionals recognize the wider impact of these root canal infections and advocate for early diagnosis and treatment," says Niazi.

"We also need to move towards integrated care, where dentists and general practitioners work together to monitor the risks through these blood markers and protect overall health. It's time to move beyond the tooth and embrace a truly holistic approach to dental care."

The study was published in the Journal of Translational Medicine.